Ernest Thompson-Seton

The most interesting of Mr. Ernest Seton-Thompson's books is still unwritten — namely, his autobiography. Few men have led a more varied existence than the author of “Wild Animals I Have Known,” but as yet only a modicum of his personal experiences has been given directly to the world, for, like most Englishmen, he does not willingly talk for publication. Indeed, this trait is, superficially at least, the most striking mark of his nationality, residence in Canada and the United States having modified the distinctive English accent which we may assume originally to have existed.

“I was born in the north of England forty-one years ago,” he said in the brief course of his autobiographical remarks, “and was educated partly in my native country and partly in Canada. After my definitive return to Canada at the end of my school-days, I spent several years knocking around the province of Manitoba, working at times as a laborer on the farms, in order to earn enough money to keep me going, and then wandering through the wilder portions with everything I owned on my back. Yes, I worked literally as a day-laborer,” and he held out his strong, nervous hands, which are bronzed by exposure, but which retain no slightest trace of these early experiences. “They don't show what they have been through, do they? The only way to get big, coarse hands is to be brought up to manual labor; otherwise as soon as you get back to your desk or studio they become normally delicate again.”

“Owing to family reasons,” the subject of this sketch is the possessor of several sets of names, by each of which he is known to a certain portion of the reading and artistic world. To the readers of his stories he is Ernest Seton-Thompson, to his friends he is Ernest Thompson Seton, while to those familiar with his purely scientific books and drawings, the latter being well represented in the Century Dictionary, he is Ernest E. T. Seton.

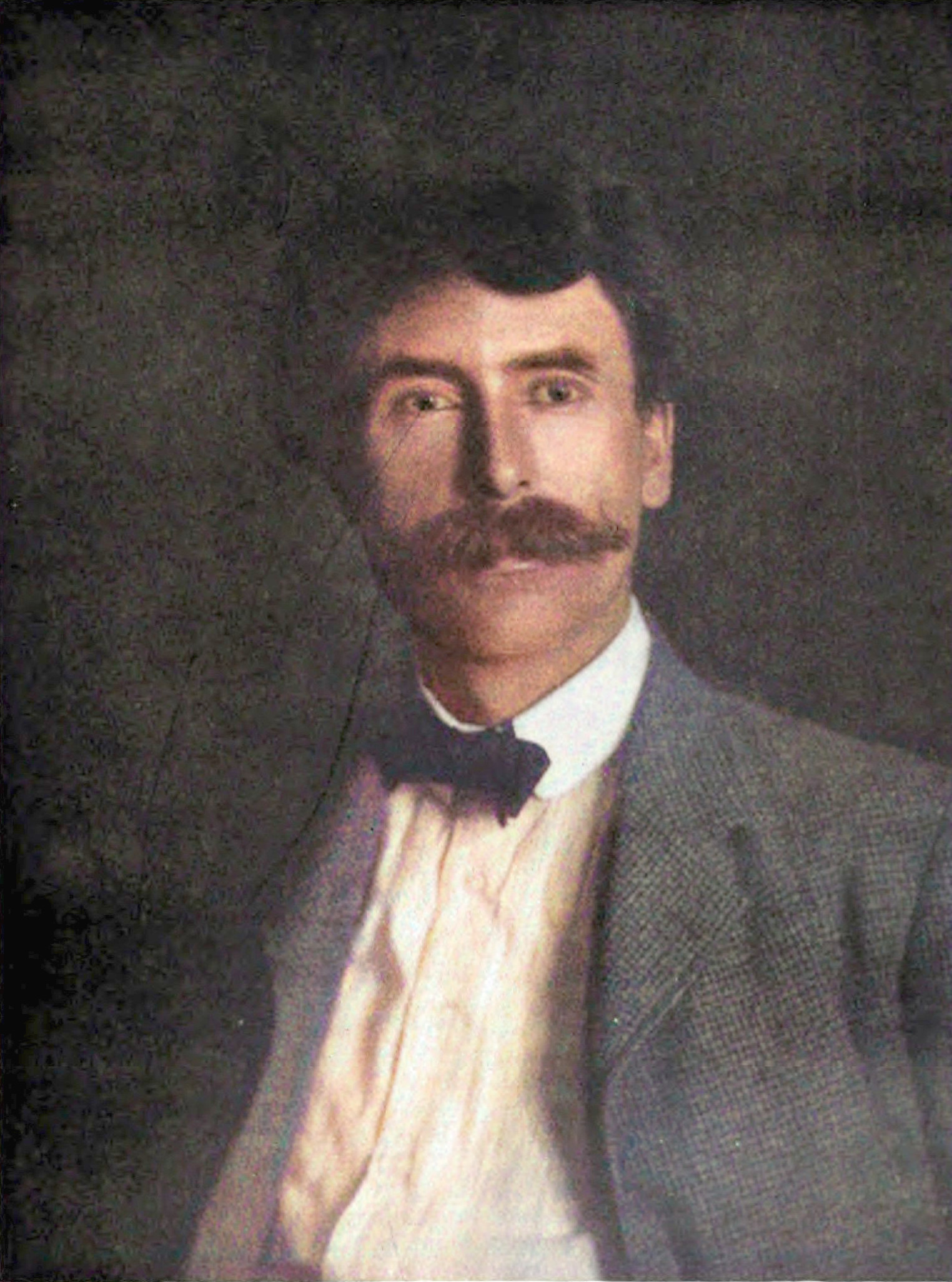

To obtain this information a series of questions were necessary, eliciting the fact that in private life the author prefers to be known by his family name of Seton — the cognomen, it seems, of an ancient Scottish family, whose American branch he represents. “Certainly never with my approval am I addressed as Thompson,” he said during the unravelling of this “nominal” complication; “that is like calling a man Gregor when his name is MacGregor. It should be written Seton-Thompson, with a hyphen.” Physically the hunter-author is ideally adapted to hardships and wanderings in the wilderness; or would it perhaps be more logical to regard his physical development as the result of such experiences? Slightly under six feet in height, he is of the order of men who distinguish themselves by phenomenal endurance rather than by feats of strength. Lithe, spare, and wiry, in other days he might have heen selected by the tribal heads for the bearing of despatches or to give warning of the enemy's approach. In reference to his hirsute adornment and clear-cut profile, Mr. Seton-Thompson has so frequently been styled a “dark-haired Paderewski” as to preclude further employment of the comparison.

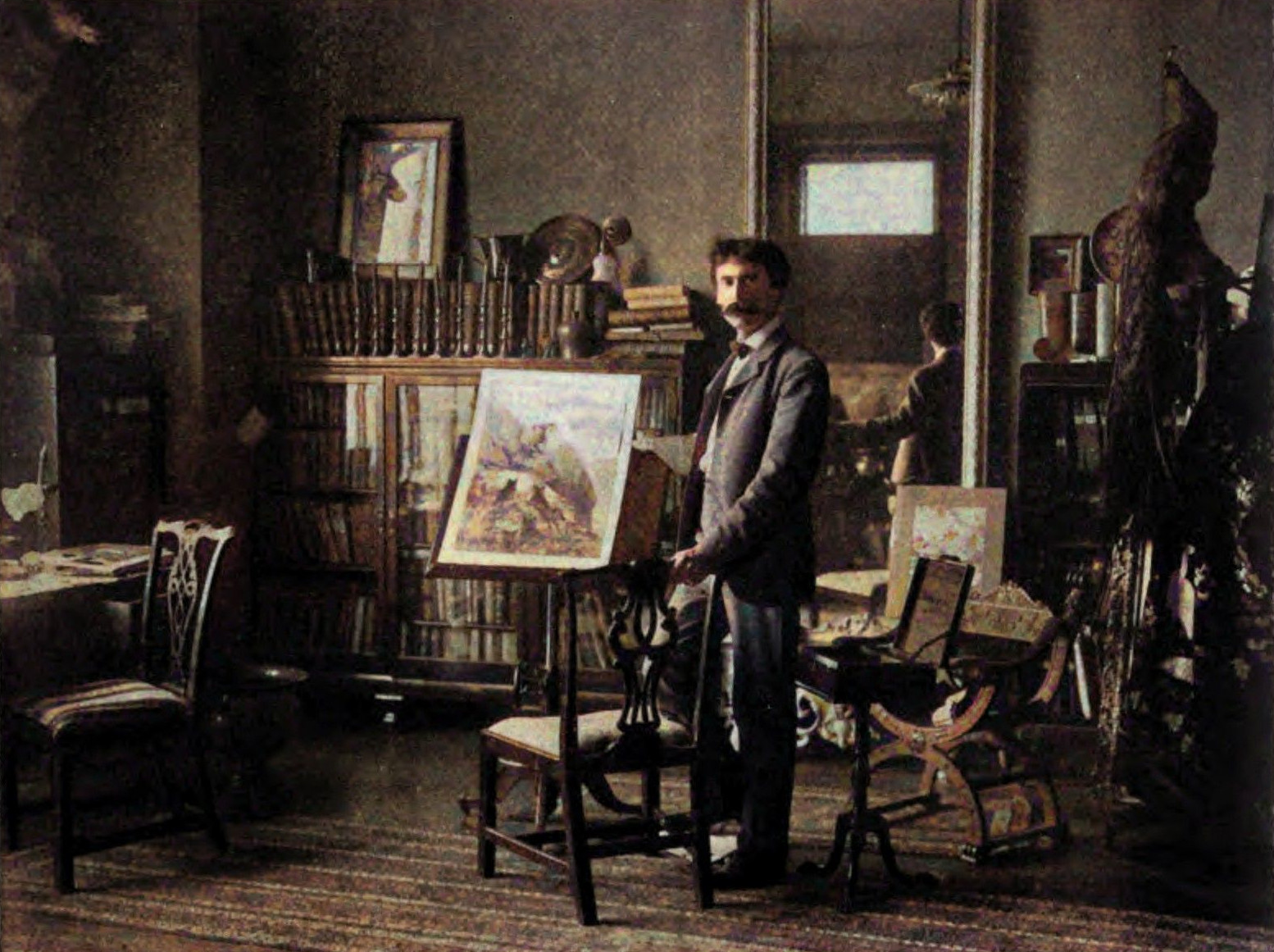

A man's surroundings are an index to his character. Mr. Seton's large, airy studio, in the front of his apartment overlooking Bryant Park, is a spot in which one may easily imagine animal stories being written. Indeed, the temptation assails the chance visitor to essay this style of literature himself. On the walls hang a number of animal drawings executed by their owner, and on the shelves stand a collection of scientific works on the fauna of various countries, together with the author's journals and his extensive collection of photographs, carefully arranged under the headings of “bears,” “wolves,” “birds,” etc. In one corner lies the great mounted head of a Rocky Mountain big-horn, from which might have been drawn the illustration for the “Cootenay Ram” on the easel opposite, save for the greater magnificence of horn in the pictured lord of the mountain. This is one of the numerous illustrations for Mr. Seton's new collection of stories, “The Lives of the Hunted,” which is to appear in the early autumn. About half of them have already been published in magazine form.

“My wife calls me a man of one idea,” said the writer, in speaking of his books, “and I suppose it is true. All my work has been done with the idea of popularizing science, of inducing people to take an interest in the animal world.”

“Which are you the most interested in, Mr. Seton, the scientific side of your work or what one may call the ‘fictional’ side?”

“The scientific — my only object in writing about animals in the story-form is to attract a class of readers who would not otherwise care to read about them.”

“Do you ever intend to write fiction?”

“No, that is entirely out of my line; I have never even attempted it.”

“I have a theory, Mr. Seton,” I said, “that the surest way to gain immortality as an author is to write about animals. Man's interest in the animal world is so spontaneous and unchanging that what interests one generation in this line is pretty sure to interest all. Don't you agree with me?”

“I really could n't say, as I have never tried another generation. However, it is true that an interest in animal legends is found among all peoples, and in some cases even the same story at widely separated points. As, for instance, the legend of ‘Reinicke Fuchs,’ that Goethe was the latest to put into literary form. The most popular treatment, however, in Germany was that of an anonymous poet of the eleventh century, for whose detection a reward was offered, as he was supposed to have caricatured the Landgraf of his province in ‘Reinicke.’ They did n't find out, however, who had written it.”

“This same story of the fox was found in France, was it not?”

“Yes, and through it the name ‘reynard’ became so popular that it quite displaced the Latin name ‘vulpes,’ that had previously been universal for the fox. None of these animal legends, however, has any scientific value; the animals in them are all treated as types, personifications of certain human qualities.”

“It is from the imaginative point of view, I should say, that Kipling's jungle stories are written, rather than from the scientific, is it not?”

“Certainly; he did n’t pretend to write anything but fiction in doing them.”

“You are acquainted with him, are you not? I have seen it stated that you told him the story of ‘Wahb’ before it appeared in the Century, and that he urged you to write it, despite your objection that it was not worth doing. Is that true?”

“It is true that I told him the story, but I don't know that that had anything to do with my writing it, as at the time it was already partly on aper.”

“Well, that is pretty accurate for a newspaper story, at all events.”

“I recently received a letter from a man in Canada,” said my host, apropos of newspaper anecdotes about celebrities, “saying that the writer knew my books and that he had read of my having been in Manitoba during a certain summer in the eighties, and inquiring whether it was not perhaps I from whom he had bought a rubber blanket for a dollar at that time. I wrote back that his supposition was probably correct, as I remembered having sold my blanket to a man in Manitoba. A few weeks later I received a clipping from a Canadian newspaper, headed ‘Forced to Sell his Blanket,’ in which an account was given of the plight to which I had been reduced, having been compelled to sell a ten-dollar blanket, said the article, for one dollar. As a matter of fact, I had bought the blanket two years before for one dollar, and had thus had the use of it all that time for nothing. Moreover, I did not sell it because I was hard up, but solely to avoid the necessity of lugging it around with me.”

I had heard indirectly of the hardships suffered by Mr. Seton in former years in the city that is now madly anxious to pour money into his lap, – or, rather, into the lap of his wife, as it is she, if report speaks truly, who treats with publishers and lecture-managers, – but much questioning was needed for the eliciting of even the outlines of that “meagre” period.

“I don't know that there is anything especially interesting to tell,” Mr. Seton kept saying in deprecating manner; “I had my privations like other men, and struggled along somehow through them, but I don't know that there is anything especially interesting in them.”

“Tell about your Madison Square experience, Ernest,” urged Mrs. Seton, who during much of my visit was busy, with pencil and ruler, with the “make-up” of her husband's new book.

“No, no, that is not worth while; besides, it has already repeatedly appeared in print,” and so I did not get to hear of the Madison Square episode.

“I first came to New York in 1883,” he said, “but could only stick it out for two years. I had n't a cent in my pocket, and for days I tramped around the town trying to get something to do, anything to keep from starving. At last, by chance, I wandered into a lithographer's and asked him for a job. On the strength of my drawings, he said he would try me, and asked me what pay I wanted. I was ready to take ten dollars a week, but I boldly demanded forty. The result was that he employed me as a lithographer at fifteen dollars a week. One day, several months later, by accident I overheard a Jew customer say to him : ‘If I could get a goot raven, I t'ink I could make ten t'ousand.’ As soon as he had left I went to the proprietor and told him I had heard what the Jew had said and that I wanted him to let me make the drawing. ‘Why, what do you know about ravens?’ he said. ‘Never mind,’ I replied; ‘you let me try and I 'll show you.’ Perhaps something in my manner impressed him with the idea that I knew what I was talking about; at all events, he told me to go ahead and try, and I went out to Central Park and drew one of the ravens. The Jew was delighted with it, and on the strength of this success I struck my boss for a raise of salary. ‘Don't you think I'm worth fifty dollars a week to you now?’ I asked him. ‘I have shown that I can do what your high-priced artists can't do, and yet you want to keep me on fifteen dollars a week.’ At last, after a lot of hemming and hawing, he agreed to come up to twenty dollars a week, but most unwillingly. For several months longer I worked on under this arrangement, and then I told him I must have another increase. He refused; so I said I would quit. When he saw I was really in earnest he offered to make it twenty-five dollars, but I stuck to what I had said, and pulled out for the West, feeling as though I never wanted to see the place again. But two years later I was back once more; this time, however, at the instigation of the Century Company, as they wanted me to make bird-drawings for the dictionary.”

“Which was your first story, Mr. Seton?”

“‘The Carberry Deer Hunt,’ which appeared in Forest and Stream in 1886. This contained the material afterward embodied in ‘The Sandhill Stag,’ although neither so extensively nor so well worked out. Oh, no; that was n't my first story, either — I forgot. ‘Way back in 1880 I had written a story called ‘The King Bird,’ but it never appeared. I have it in the box yonder with other unpublished manuscripts, and some day I may find out what is the matter with it and get it into shape that satisfies me.”

“How did you first become generally known, Mr. Seton; was it through one story in particular?”

“No; that is a very hard thing to do, to make one's reputation by a magazine story. After the Forest and Stream story I continued to write for numerous publications, — ‘The Drummer on Snow-Shoes,’ which was the precursor of ‘Red Ruff,’ appearing in St. Nicholas. in 1887, and others, such as ‘The True Story of a Little Gray Rabbit,’ the prototype of ‘Molly Cotton-Tail,’ and others following at short intervals; but it was not till the publication of a number of these in book form in 1898, under the name of ‘Wild Animals I Have Known,’ that I really made a name for myself. And even then it was gradual work, and I have, besides, followed it up by a new book every year.”

“You know, I suppose,” said Mrs. Seton, “that my husband is official naturalist of Manitoba? He was given the position as the result of his two books, ‘The Birds of Manitoba’ and ‘The Mammals of Manitoba,’ which were published in 1891 and 1892. During the World's Fair he represented the province in Chicago; indeed, the position was created for him for that occasion.”

“I have sometimes been accused of plagiarizing the idea of animal stories from Kipling,” remarked Mr. Seton toward the end of my visit, when the conversation had again come round to the pervasive English author, “but, as a matter of fact, the first time I ever even heard his name was in 1894, when a friend of mine said to me, apropos of my own stories, ‘You ought to read the animal tales of a man named Kipling.’ It was in that way that I first became acquainted with ‘The Jungle Book.’”