At Windygoul with Ernest Thompson Seton

A more nearly ideal summer workshop than Windygoul, the woodland home of the biographer of Lobo, Wahb, and the Sandhill Stag, poet could not conjure. Through the quaint village of Coscob, Conn., favorite haunt of artists, over a winding road flanked with wild cherry and tree of varied leaf, the “Hearse,” the station’s one passenger vehicle, is wont to jog the wayfarer until it comes abruptly to imposing stone pillars with great wrought-iron gates in the centres of whose bronze shields two brass “S’s” are blazoned.

“There's Mr. Seton's place!” cries the liliputian Jehu, and in the absence of a lodge-keeper, he is off his seat, the gates swing in, and soon we are lost in an aisle of greenery whose Gothic arches recall Bryant's famous line:

The groves were God's first temples.

A break in the foliage at length reveals glint of water.

“The lakes!” cried the ebony driver. “There's three of 'em and a cave. Golly! It’s a cool place to swim.” The coon’s ruby lips smacked, evidently in memory of many a surreptitious plunge, for does not the framed placard at the entrance warn the trespasser?

“Mr. Seton, he’s a big man — he is. He's got a lot of animals. He's going to have a zoological garden. Listen! There’s the peacock.”

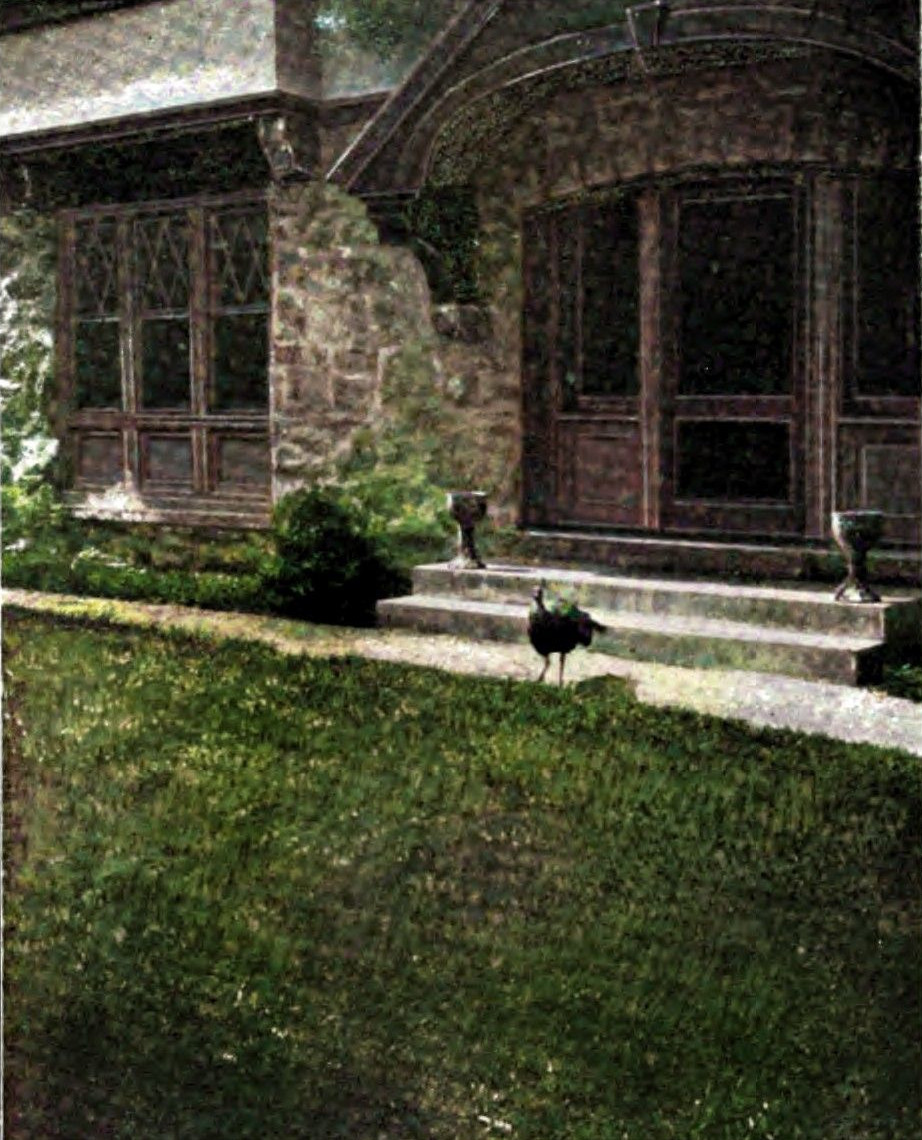

Hewn of stone and perched like a nest on the edge of a cliff overlooking a wooded ravine is the house, a veritable lodge in the wilderness. The picturesque entrance opens upon a rolling sward fringed with hemlock, over whose tops, on a clear day, a glimpse may be had of President Roosevelt’s home at Oyster Bay. On adjacent cliffs, which the completed house is designed some day to crown, are pitched two tents, one of which was personally used for three years by Thunderbolt, Chief of the Sioux tribe of Indians.[1]

“There’s Mr. Seton,” beamed the ebony guide, and the “Hearse’ suddenly ceased to creak.

From the shadow of the Tepee came the tall, swinging form of the hunter, artist, author, who has probably come face to face with greater numbers of American youth than any man of his time, and whose “Wild Animals I Have Known” has done more, perhaps, than the world’s anti-vivisectionists to preserve animal life. A slouch hat shaded his eyes, that have confronted so fearlessly, yet compassionately, the hunted life of plain and mountain, canyon and stream. Satisfied that the new biped was harmless, into the shrine of his Lares and Penates we were taken to learn how the stories that charm a reading world are fashioned.

This is the owner’s first summer at Windygoul. “Since April,” he said, “I have been back and forth from my city studio, and when I return from the Rockies in August I look forward here to glorious autumn days of work and play. For some years we have been looking far and wide for a home where Mrs. Seton and I could have something of the out-door life and animal companionship to which we are accustomed, and at the same time be not too far from the city. We had about despaired when we came upon this old Indian reservation. The descendants of the original owners still live in the vicinity.”

What more fitting that the happy hunting ground of a vanished Red Man should fall to one in such sympathetic touch with his life and his traditions!

Windygoul covers 120 acres of wildly luxuriant vegetation. There are more than four miles of drives. Three natural lakes of ten miles area have been deepened and cleansed, and the original islands here and there more sharply defined. Otherwise Nature is the architect.

The woods of Windygoul abound in wild gray and red squirrel, rabbits, and every species of bird, while the lakes are filled with small fish and the shores rich in wild duck. A peacock and his lady-love, turtles, and various small animal friends have been sent to Mr. Seton; and when the extent of his forest home is known, wild rarities from the Rockies will doubtless be forwarded to Windygoul by guide, trapper, and scientific chums of the gone days when the heroes of his stories were making history. There are no deer. “Wild deer,” said Mr. Seton, “will not come near man, and the tame are too vicious and dangerous to have about.” Sitting on the broad veranda, hung in rugs and Indian blankets and decorated with trophies of the plains, the chronicler of Silverspot, as we chatted, listened and responded to the cry of every winged thing in the encircling wood.

“There’s a yellow-winged woodpecker! Listen to the crows — a mother is feeding her young. She said but one word — ‘Allright!’”

On an arm of an old oak embracing a corner of the veranda the gorgeous peacock elects to pass his sleeping hours, while all that flutters in grass or tree is on more than speaking acquaintance with the master of Windygoul.

“Somehow,” said Mr. Seton, “I find it very difficult to write these days. I thought in the city that I would do so much when I got settled here, but I want to be out-doors all the time.” The click of a typewriter came reprovingly from an upper den. “I ought to be at work now, but I would rather row on the lake, wouldn’t you?”

Down the cliffs, stubby with laurel — a fire once swept over Windygoul, reducing the laurel-trees to brushwood — across the peacock’s domain, freshly sown with grass-seed, to the lake we went, and, fortified with cushions and armed with a kodak, were soon gliding over its rippling surface that mirrored as perfect a day in June as ever Lowell versed.

“You will observe,” said, exultantly, the decoyer of Lobo, “that there are no mosquitoes. Small fish and mosquitoes cannot live together; mosquitoes cannot breed on dry land. By stocking these lakes with small fish I put an end to the pests. Fish and kerosening the surface are infallible mosquito executioners.”

Dense wood and towering cliff encircle, like a richly embossed frame, the lakes dotted with tiny islands and linked by narrows through which the trusty skiff deftly glides while one yields to the dreamy languor of wood and sky and stream, until suddenly a roar of artillery startles the sylvan silence.

“Blasting on the Palisades,” said the rower, focussing wild ducks on a rock. “Yes, it is hard to realize, until wakened in some such rude way,” he apologized, “that Greater New York is so near.”

“It will take some time to improve Windygoul,” was ventured, vision of notable American country-gentleman places intruding upon this God-given spot.

“No artificiality shall ever mar Windygoul,” he said, thoughtfully. “It is home for wild animal life as much as for myself. I want every strange animal, awing or a foot, to feel welcome here.”

Fastened to an old tree on an island was a wooden box.

“Was it there when you came?”

“I made that house,” he smiled, “for an old mother owl. I thought she might find it handy. The woods are full of owls.”

“Pavo! Pavo!” rose over Rimrock, a lofty cliff dipping into the lake at its deepest point.

“Pavo! Pavo!” called back the man at the oars. “The peacock's call,” he explained, “is the bird's Latin name.”

As the skiff rounded an island there rose in the distance a bridge connecting a road crossing the stream.

“Ah, you should see it in May,” said Mr. Seton. “It is made of natural dogwood, and in season the whole is one mass of bloom.”

Leaving the lakes basking in afternoon shadow, we tarried in Thunderbolt's tent, round whose open fire Mr. Seton and his clever wife, companion of many a Western venture, delightfully recorded in “A Woman Tenderfoot in the Rockies,” are wont to sit, Indian fashion, when night falls, and talk over with “the boys” the old days on the plains.

The tent is decorated on the outside with the Chief's coat-of-arms — alternating circles of black and yellow beads, from which float, in lieu of scalps, bits of horse's tail. An Indian never parts with a scalp. This decoration outlines either side of the tent’s entrance, which is laced together with pins skilfully whittled of pine twigs, the handles preserving the native bark. The open top is browned with the smoke of many a council of peace, and the canvas, which is impervious to rain, bears impress of its weathering. In the centre, sunken in the naked ground, is a stone receptacle for the fire.

“Let me get some boughs and show you how it burns,” said the heir of Thunderbolt's discarded wigwam, when a typewriter, with an undecipherable passage, recalled the truant author to his workshop.

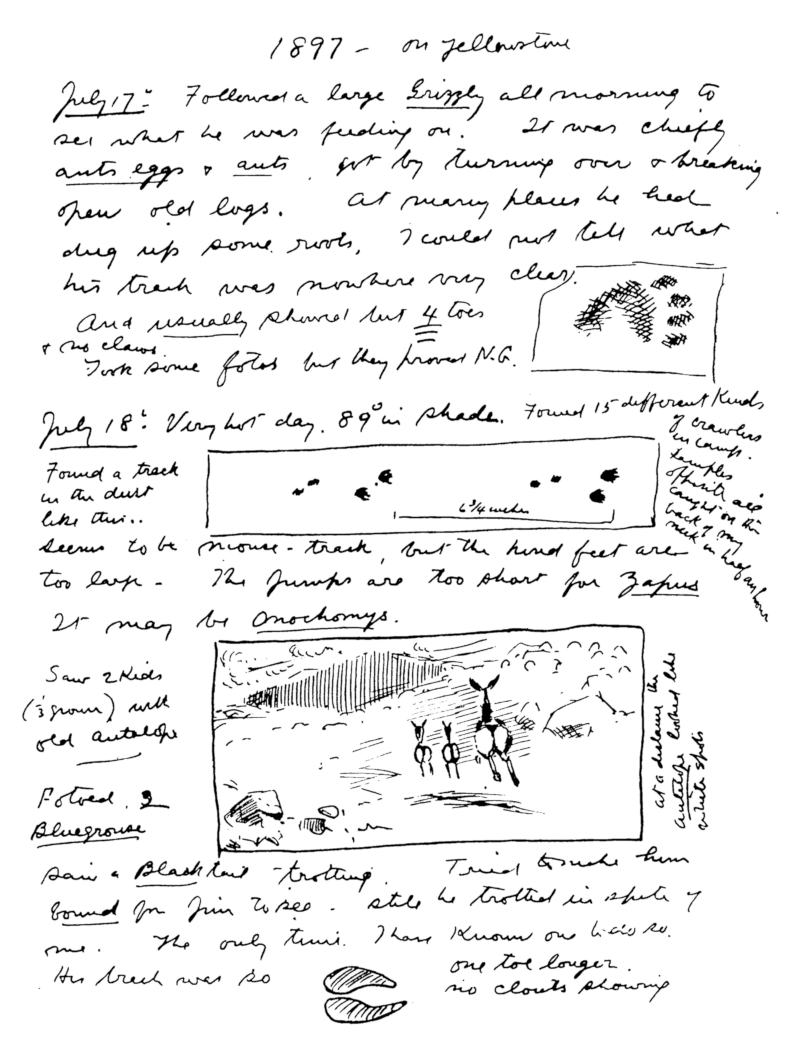

No writer, perhaps, has so nearly unique a working library — a library of his own writing. For more than twenty years he has kept journals of his hunting expeditions and scientific explorations in Canada, the Rocky Mountains, and the Western plains. They reveal, as could no biography or history, the range and the minutiae of his observation, and the painstaking care, the scientific accuracy that characterize his stories and give them uncommon value. A bulky volume is the “Journal,” beginning in 1880, each day’s observation written in clean, legible script, and here and there profusely illustrated with pencil sketches. Here is the pictorial beginning of the Sandhill Stag story — three deer in various attitudes of flight.

“I noticed,” said Mr. Seton, his finger on the second deer, “that, while running at full speed, it suddenly stopped, and, throwing back its antlers, scratched its hind hoof.” And there, in a few graphic strokes of the pencil, was the incident recorded for future use.

“Do you find the ‘Journal’ now of much practical use?”

“Messrs. Gould, Morgan, Vanderbilt, and Rockefeller once made a bid for it,” said he, solemnly, “but the trust had not enough money to buy it.”

It is practically the mine out of which his fame and fortune have been quarried, and as he tenderly turned its yellowed pages between the scarred and battered covers, face and voice freshened with old memories.

“Yes, I think keeping a journal excellent practice,” he continued. “It is good discipline to write down daily what one observes, and often it is invaluable for reference.”

His is the most complete, if not the only, pictorial animal library in the world. There are more than fifty volumes, alphabetically arranged and appropriately labelled.

“If you don’t have a thing when you want it.” he said, “you don't possess it.”

Under the caption of Nests, Horses, Buffalo, Deer, Lynx, Small Cats, Dogs, Cattle, Streams, Snow, Landscape, Figures are portfolios upon portfolios filled with pictures relating to these and kindred subjects in steel and wood engraving, pencil, ink, and water color, not to forget advertisement cards. Nothing relating to animal life is apparently too small, too inconsequent to be duly filed by this systematic worker.

In jars and vials are preserved all sorts of curious animal and plant life. Finding in a deer an encysted tapeworm, Mr. Seton preserved it as a curious discovery, until a well-known bacteriologist and microzoologist was overjoyed to recognize in it the one missing link necessary to the completion of his own collection. Extended and of great value are the portfolios of his own animal drawings and great maps of animal tracks, secured, for the most part, by Mrs. Seton at the Zoological Garden at Bronx Park.

“The Zoological Garden is of great service to me,” said Mr. Seton, “when I can steal away from lecturing and writing and spend a few hours there. I depend upon Mrs. Seton. She often goes into the brown bear's cage, and, with the keeper's assistance, is able, by painting Bruno's feet with black paint or printers’ ink, and coaxing him to walk back and forth on a carpet of light-brown paper, to secure valuable footprints. These studies of animal footprints enable me, in hunting, to detect an animal’s presence and trace him to his lair.”

In a bow-window room swinging over the main entrance are stored his pencil sketches, together with shelves of letter-files — many personal tributes from the world’s foremost scientists and men of letters — and volumes and volumes of notes, including two huge octavos filled with data preparatory to the writing of his next book — “Big Game of North America.” And when the snow flies, back to the city studio go the “properties” of the first of American animal story-tellers.

“In writing, what do you find the most difficult?” was asked.

“To put what I want to say in 4,000 words, then cut it down to 2,000, still preserving what I would not leave unsaid,” was the reply.

- ↑ It's mistake. Lida Rose McCabe bad heared. Original owner was Thunder Bull, a chief of the Cheyennes.