The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1902 (series)

Součástí této série, byl i článek o návštěvě prvního kmene Setonových Indiánů, který vzniknul na jejich základě. Tento kmen si vytvořily během svého letního pobytu děti ze dětské ozdravovny (Fresh-Air Home) v Summitu (New Jersey), pod záštitou její ředitelky Lydie Crane, o níž se článek rovněž zmiňuje.

The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1902

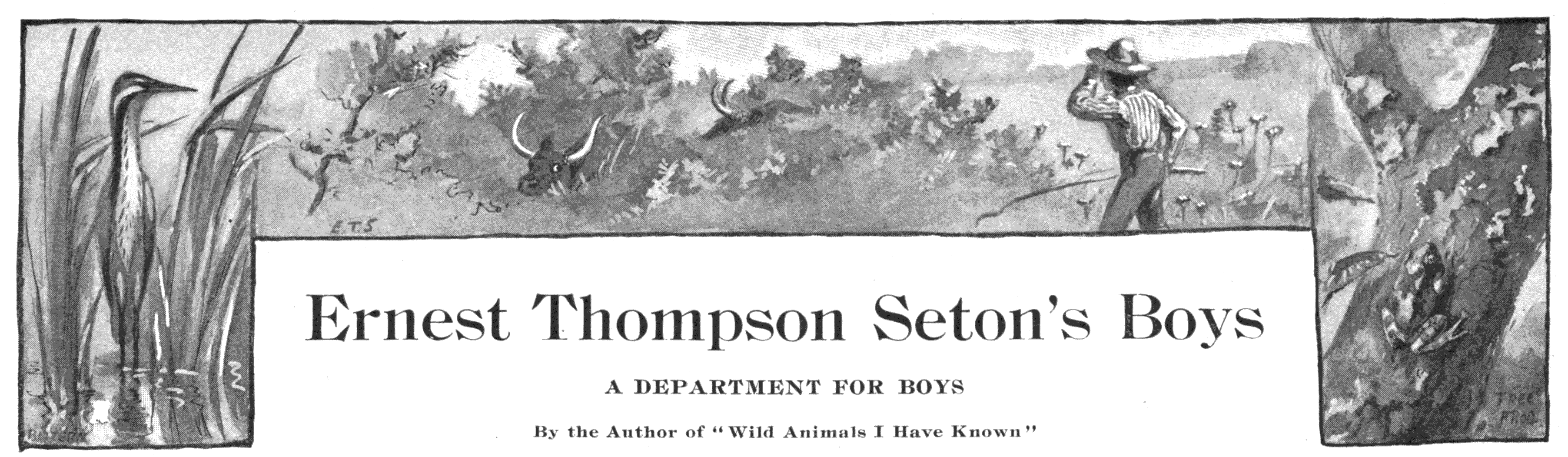

Next Month We Shall Begin “Ernest Thompson Seton’s Boys”

That will be the title under which the author of “Wild Animals I Have Known” will start his department for boys, with all the text written by Mr. Seton and all the pictures made by him. Every line and picture will breathe of “the open” which Mr. Seton knows so well and pictures so clearly.

From the very start Mr. Seton and the thousands of boys who will follow him will begin in the footprints of wild animals, hunting them and studying their interesting habits and homes. The fact that he is now having a real teepee built by real Indians savors of some exciting times ahead for the boys.

I. – ON TRACKS

The New Department of “American Woodcraft” for Boys: By the Author of “Wild Animals I Have Known”

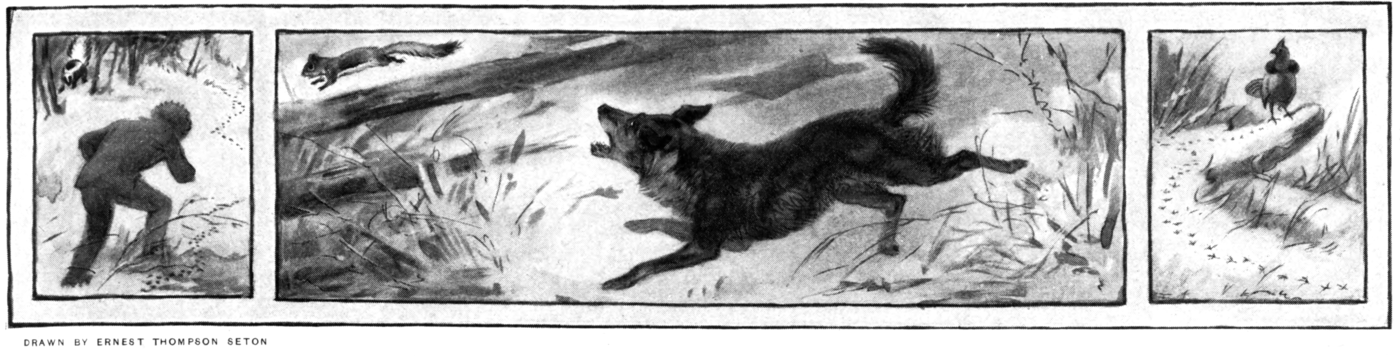

Most boys have the idea that wild animals are very rare now, or that you must go into the far West to find them. While this is true of some of the large kinds, it is yet safe to say that any one in the Eastern States can, within five miles, and usually much less, get into a region where he may discover some wild creatures. He may walk through a place again and again without seeing anything alive except a few birds, but he may be sure there were many bright eyes and keen ears and noses that were observing him and fully taking in the fact that their deadly enemy was passing near. Especially at night or late in the evening is this the case, for then the wild Fourfoots are on the move, and the hundreds of these that once used to roam by daylight have either been killed off, or have learned to come out only at night when men cannot see them. There may be many of these left in our little woods, and yet, unless knowing just how to look, one may pass many times and have no idea of

their existence.

Most boys have the idea that wild animals are very rare now, or that you must go into the far West to find them. While this is true of some of the large kinds, it is yet safe to say that any one in the Eastern States can, within five miles, and usually much less, get into a region where he may discover some wild creatures. He may walk through a place again and again without seeing anything alive except a few birds, but he may be sure there were many bright eyes and keen ears and noses that were observing him and fully taking in the fact that their deadly enemy was passing near. Especially at night or late in the evening is this the case, for then the wild Fourfoots are on the move, and the hundreds of these that once used to roam by daylight have either been killed off, or have learned to come out only at night when men cannot see them. There may be many of these left in our little woods, and yet, unless knowing just how to look, one may pass many times and have no idea of

their existence.

It is unfortunate for it, though lucky for the naturalist, that wherever a Fourfoot goes it leaves behind a little written account of its visit, its name, the time, the place whence it came, what it did, and when and whither it went away. We can find these accounts and read them and thus learn of the numbers and kinds of our wild neighbors. These “manuscripts”, though I should rather perhaps call them “pedoscripts”, are, of course, the tracks which the animals leave in the mud, snow or dust.

Each animal makes its own kind of track: no two make exactly the same. The track of a ’Coon is never like that of a Fox, and the track of a Fox is readily distinguished from that of a Rabbit or small Dog. And more than that, the tracks of one ’Coon may differ from that of his own brother, so that one sometimes distinguish the tracks of a given individual, and by seeing it on different occasions get something like an insight into its life. Thus, a famous Grizzly in the West was known by his track. One of his toes had been cut off by a trap, and the difference that made in the mark was easy to see. To come nearer home, our common animals sometimes have unpleasant experiences with steel traps. The marks of these on their feet often add a peculiarity that identifies the animal; in other cases the track is extra large or small, or is crooked, but it always keeps the main features of its kind. The track of one sort of animal rarely need be mistaken for that of another, and the A B C of tracking is to learn the chief kinds of footmarks that are to be found in your region. The way to learn tracks is to draw those that you find, always sketching them right from Nature, never from memory, and it is always best to make them exactly life-size.

The snow is the best for tracking when you wish to follow the animal a long way and see what it is doing. But the snow rarely gives a perfect individual track. The mud and the dry dust, if not too deep, are much better for details. I have tried many ways of getting records of tracks, and have some interesting results, especially among domestic animals. The Dog and Cat are the creatures whose tracks are likely to be first met with. But they are most aggravating subjects when one tries to get tracks from them. My first attempts were made with modeling-clay spread out thin on a tray; but both Dog and Cat would either bound over the tray or wriggle or squirm or scratch it in long furrows, and, in short, do anything but walk calmly across and leave a few good impressions. One cannot take the animal’s paw and make an imprint. That is sure to be wrong. The creature must do it itself and in its own way, and the track is sure to be spoiled if the animal is hurt or scared. Still, patience will surely win.

A good track, once secured, can be cast in plaster and kept for future use. While following tracks in Nature one soon realizes that not more than one in a thousand of those made is perfect. The accidents are so numerous that most of them are spoiled. It must be taken for granted, therefore, that a good many will be made in the modeling wax or clay before getting a perfect set showing all the details and characteristics.

A thin coat of dry flour, plaster, dust or other fine powder on a board gives a good impression,but it is difficult to make record of, sketching and photographing being the only ways. I have got a Cat to make its own records by blacking its feet, then making it trot over some papers, and these are easier to read if the ink on the hindfeet be a different color from that on the front. It is well, also, to clean the animal’s feet afterward before it is allowed to enter the house.

A number of boys recently offered their help in getting a series of Cat paw prints. I gave them an idea of how to go about it. Their father kept a general country store. So while one boy mixed a lot of lampblack to the proper consistency, another helped himself to a roll of wall paper and spread it in a long corridor with the white side up, and the third went out and captured a large Tomcat. They now painted Tom’s feet with the lampblack and chased him up and down the corridor till he was half crazy. Whenever they could catch him they touched up his feet afresh and set him puffing and snorting over the paper. When they brought me the roll it was thickly spotted over with tracks — most of them mere smears. Some, where Tom had slipped, were six inches long. The first after each fresh painting were too dark, and the last too faint, but still among the hundreds there were one or two good ones. This trifling success aroused the boys to high enthusiasm. At the beginning their energy had far overtopped their discretion, but now discretion dropped clear out of sight. They wished to beat their record, so they fairly soaked the Cat’s feet and legs in paint. Tom was, of course, thoroughly disgusted with the whole thing; he made a frantic jump and escaped through a transom, then upstairs and so ended his troubles; but he ran over a white bedspread, where he left a beautiful trail, after which the boys’ troubles began.

Most Cats object strenuously to having their feet blackened, and an easier way is to

lay a large piece of lampblacked or printer’s-inked paper so that the Cat will walk over that first and then over the white paper. But these methods are not possible with wild animals. They will have nothing to do with your white and black papers. Even in menageries these are usually failures. It is very rarely that tracks in the mud are perfect enough or handy to be cast in plaster. As a matter of practice, I have found that sketching is the most reliable way.

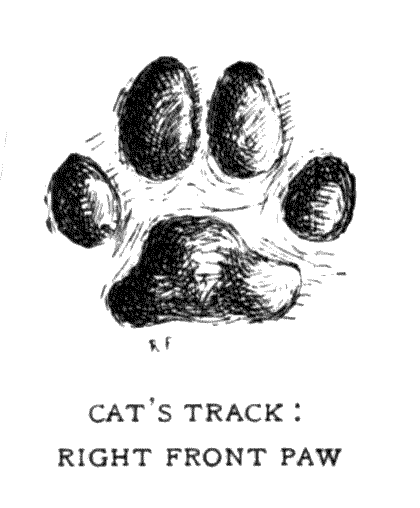

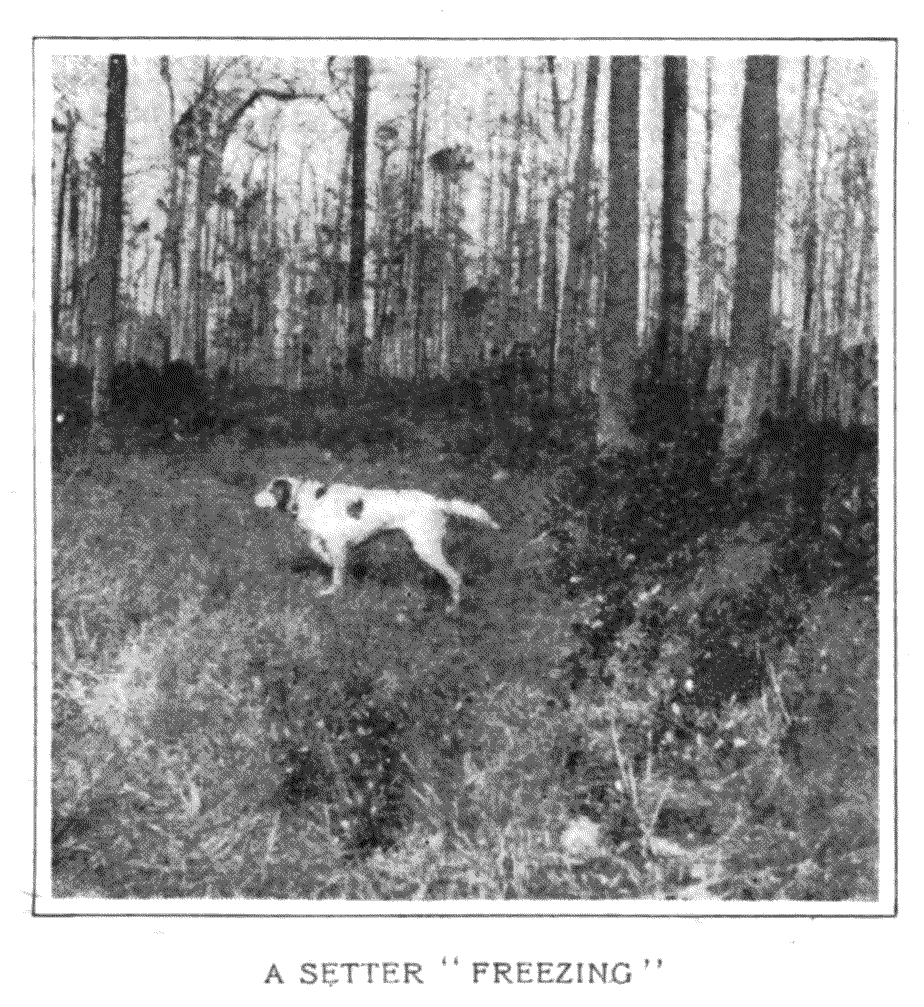

Of course the first animal tracks one is likely to see are those of Dogs and Cats, and these are good to begin with. The Cat is usually taken by the scientists as an example of a perfect animal. All its muscles and bones are of the highest type for activity and strength. Its track also affords a good study of what an animal’s track should be, and in studying it we should remember that every curve and quirk has a history and a meaning.

Of course the first animal tracks one is likely to see are those of Dogs and Cats, and these are good to begin with. The Cat is usually taken by the scientists as an example of a perfect animal. All its muscles and bones are of the highest type for activity and strength. Its track also affords a good study of what an animal’s track should be, and in studying it we should remember that every curve and quirk has a history and a meaning.

At first it seems that the toes are in two exact pairs; but you will find that they are arranged much like the fingers of a hand. The Cat’s thumb is so short and set so high up that it leaves no track. The two middle fingers are nearly alike, but the inner of these is always a little longer, as with us; the two outer ones look alike, but again as with us, the one next the thumb is larger.

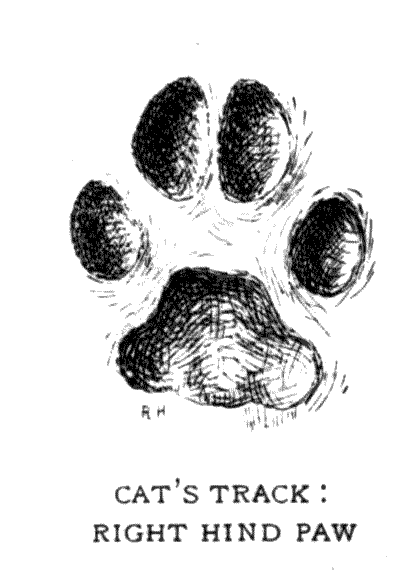

On the hindfoot the Cat has but four toes, and these correspond nearly to the arrangement of those on the front foot.

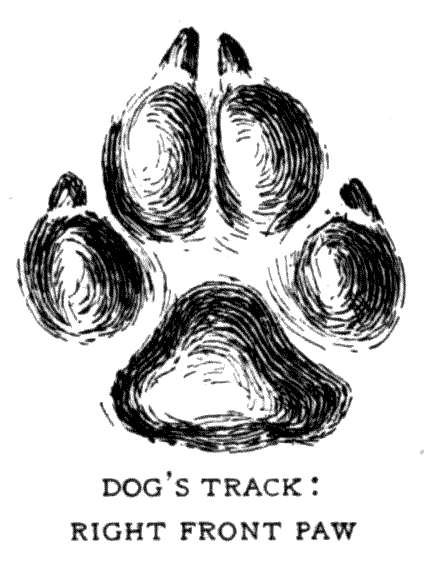

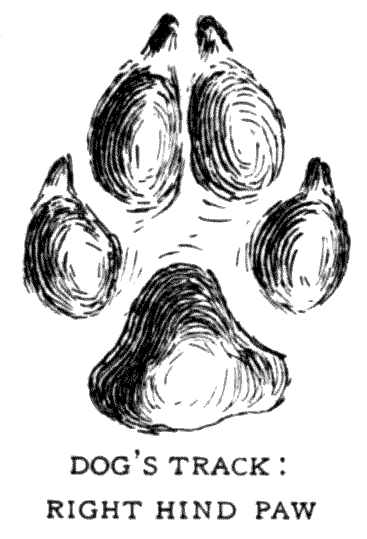

The Dog’s track differs from the Cat's first in showing the claws. The Cat’s claws are perfect. They can be drawn back out of sight when not in use. The Dog’s are more like hoofs; they are always out, and leave their marks in the track.

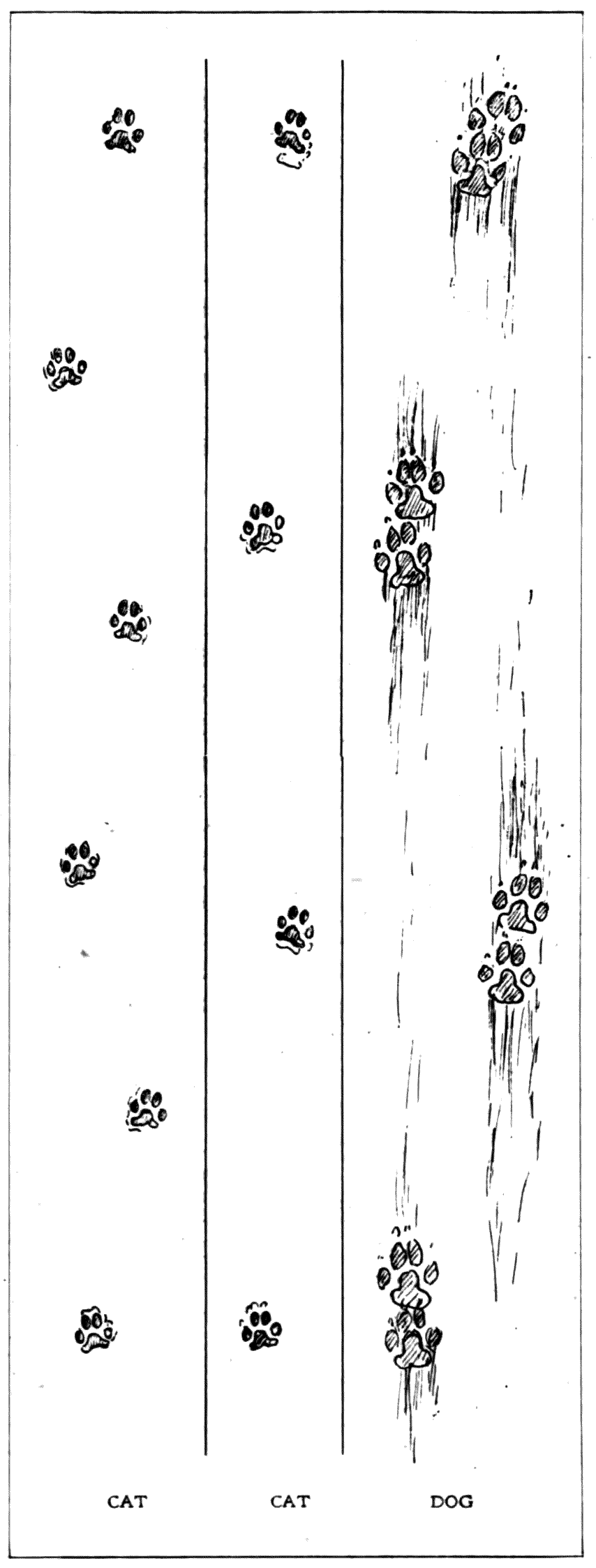

The trails of a Dog and Cat put together for comparison are shown on this page. The first thing that strikes us is that the Cat walks as though it had two feet, whereas the Dog shows the doubling of the track at each step. Of course the Cat’s track was also doubled, but the hindfoot went exactly on the mark left by the front foot, so that there seems to be but one. This is perfect tracking and it is a great advantage to the animals that must hunt for a living. There are several reasons why this is so. A wagon whose hind wheels do not follow exactly the track of the front wheels is a hard wagon to draw in sand, mud or snow; so also it is easier walking if the Cat going through snow or sand has learned to set the hindfeet in the mark made by the front feet.

The trails of a Dog and Cat put together for comparison are shown on this page. The first thing that strikes us is that the Cat walks as though it had two feet, whereas the Dog shows the doubling of the track at each step. Of course the Cat’s track was also doubled, but the hindfoot went exactly on the mark left by the front foot, so that there seems to be but one. This is perfect tracking and it is a great advantage to the animals that must hunt for a living. There are several reasons why this is so. A wagon whose hind wheels do not follow exactly the track of the front wheels is a hard wagon to draw in sand, mud or snow; so also it is easier walking if the Cat going through snow or sand has learned to set the hindfeet in the mark made by the front feet.

But there is another reason and a better one. The Cat sneaking through the underbrush after its prey must go in silence. It can see out of the corner of one eye where to set down the front feet so as not to crush a dry stick or leaf, but it cannot watch its hindfeet. However. it does not need to do so; the hindfeet are so well trained that they go exactly into the safe places already chosen for the front feet, and thus the Cat moves in perfect silence. All wild animals that sneak after their prey do thus; no doubt the Dog did at one time, just as the Wolf does to-day, but he has lived so long in town and walked so much on sidewalks that he has forgotten the proper way, and so is a very noisy walker in the woods. The Cat is little changed in habits since it came to live with man. It is still a hunter and walks as it ought.

In studying these things one must always keep in mind the great individual variation. For example, not only is the track of a Cat never exactly like that of any other animal, but no two Cat tracks are exactly alike, and the track made by one of the Cat‘s feet is never exactly like that made by another of its feet.

A third striking difference between the tracks of Dog and Cat is that most Dogs drag theirtoes. This shows clearly if there are five or six inches of snow. A Cat lifts its feet neatly and clear of whatever it is walking in.

In trotting, a Dog’s track is usually like its walking track with the steps nearly double as long, but sometimes it goes with its body diagonally, apparently so that its feet will not interfere, and this shows another variation of the trail.

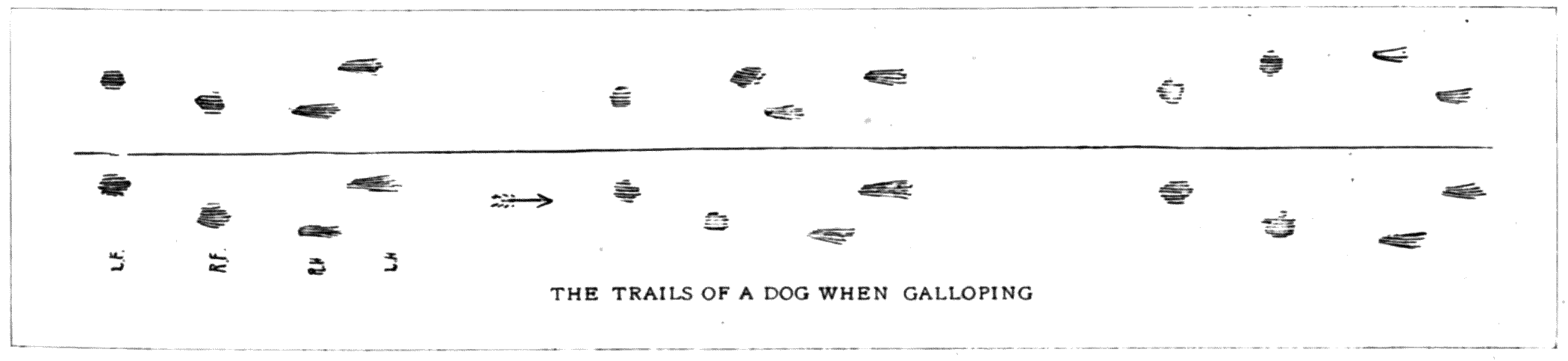

A dog galloping goes as shown on page 15. It will be seen that the hindfeet overreach the forefeet each time, and track farther, as is the case with all bounding animals. The right forepaw is ahead of the left at each bound. This is what I should call a right-handed gallop. Some Dogs are left-handed and always run with the left paw ahead. Then again, some Dogs will do both ways within a short distance. In the upper part of the same illustration is a trail that shows where a Dog changed thus from right to left.

A dog galloping goes as shown on page 15. It will be seen that the hindfeet overreach the forefeet each time, and track farther, as is the case with all bounding animals. The right forepaw is ahead of the left at each bound. This is what I should call a right-handed gallop. Some Dogs are left-handed and always run with the left paw ahead. Then again, some Dogs will do both ways within a short distance. In the upper part of the same illustration is a trail that shows where a Dog changed thus from right to left.

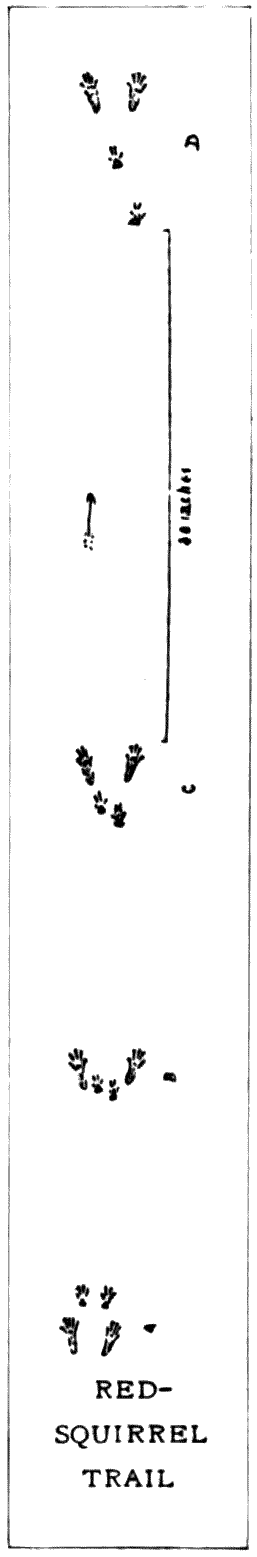

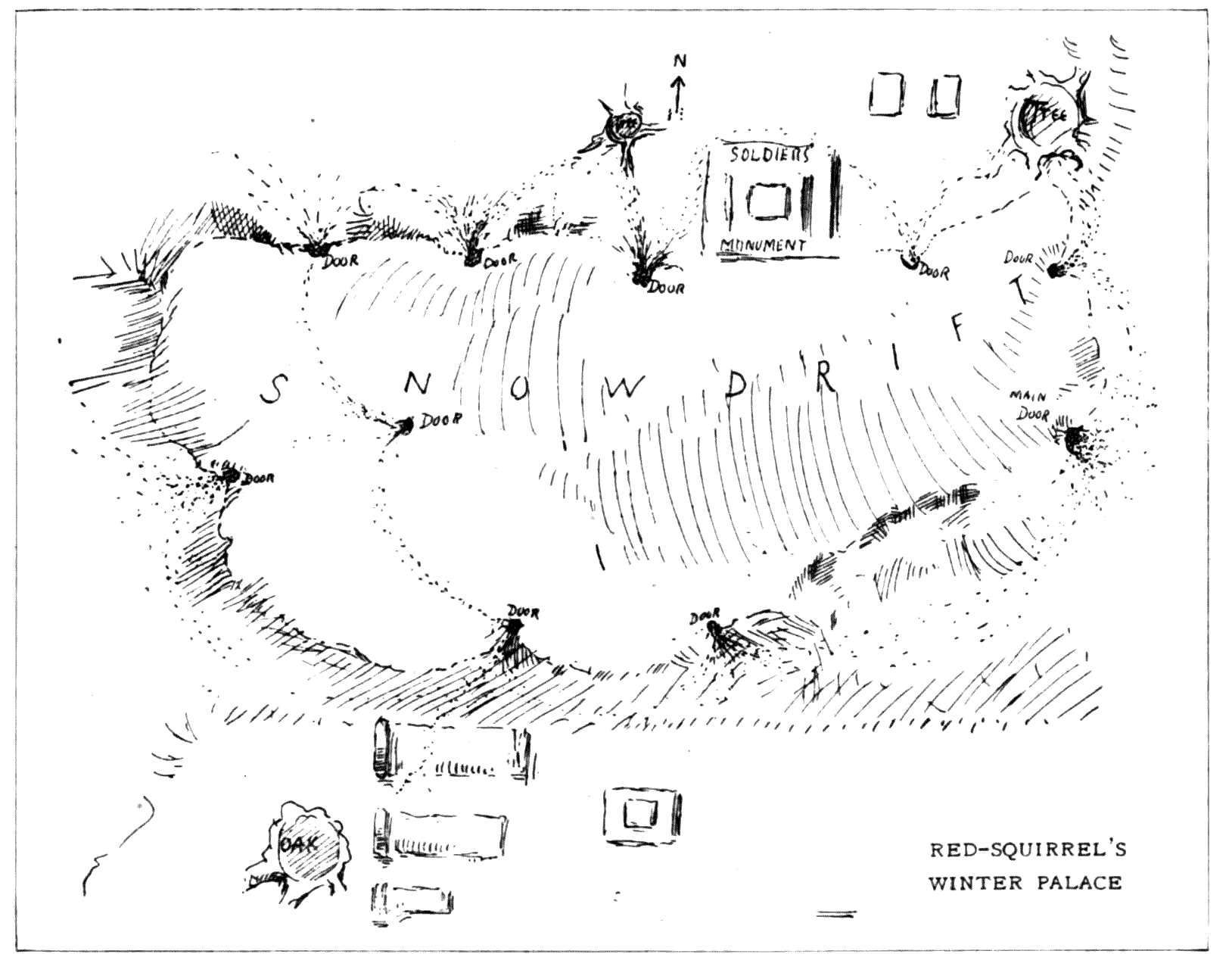

One of the commonest of the truly wild animals still found generally in the Northeastern States is the Red-Squirrel. It is a remarkably hardy, active and vigorous animal. It has succeeded in maintaining itself in spite of settlement and deforesting, chiefly because it can live in holes in the ground. As a rule the truly forest animals are the first to fly before the settler. The ones that hold out the longest are those that cling to Mother Earth as a final refuge, and this the Red-Squirrel does very successfully.

One of the commonest of the truly wild animals still found generally in the Northeastern States is the Red-Squirrel. It is a remarkably hardy, active and vigorous animal. It has succeeded in maintaining itself in spite of settlement and deforesting, chiefly because it can live in holes in the ground. As a rule the truly forest animals are the first to fly before the settler. The ones that hold out the longest are those that cling to Mother Earth as a final refuge, and this the Red-Squirrel does very successfully.

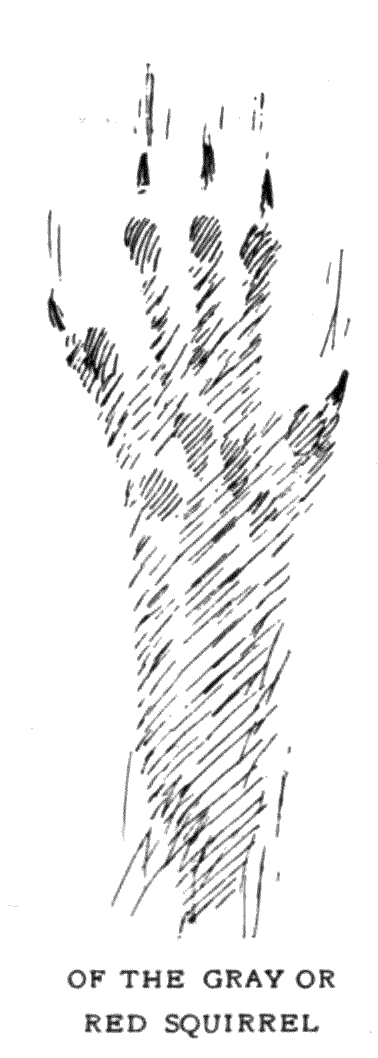

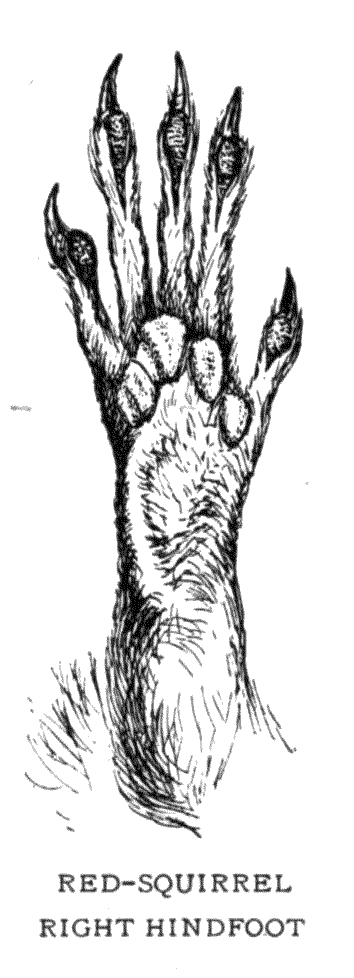

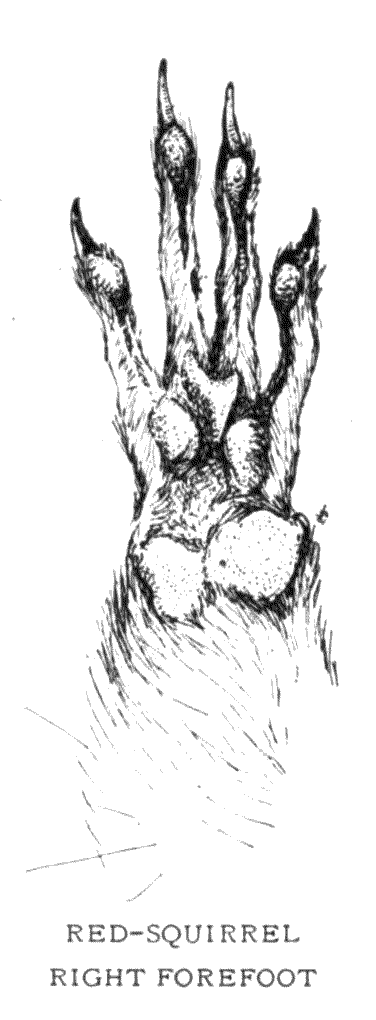

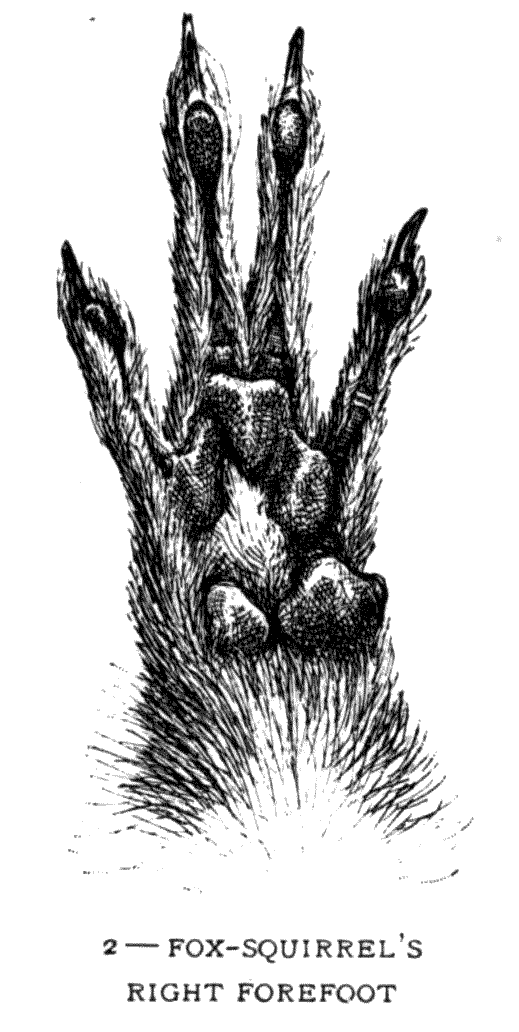

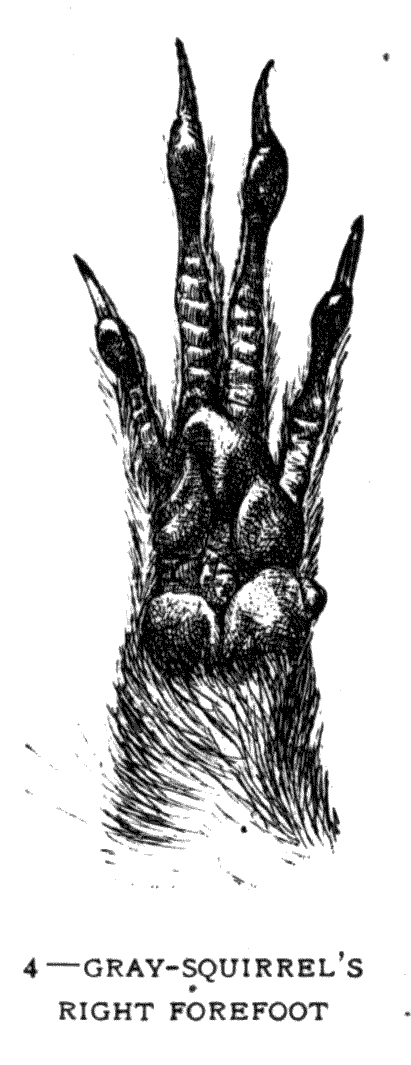

The tracks of the common Northeastern Squirrels are alike in general features, but differ in size and details. A Red-Squirrel’s hindfoot is about 2 inches long, a Gray-Squirrel’s about 2½ inches, and a Fox-Squirrel’s nearly 3 inches.

Here is the paw of a Red-Squirrel showing the sole of the hindfoot covered with hair. The Gray and Fox Squirrels have a naked heel-pad, but it rarely shows in the track.

The hind track of a Squirrel shows five toes, but the fore track only four — the thumb of the forepaw being so small that it is like a knob and does not count.

Now to go back to the woods near your city. If I were seeking for animals at such a place I should set about taking the census of the Fourfoots by looking for tracks and signs — beginning first along the bare muddy or sandy edges of the brooks or ponds, if there are any,and particularly near large old trees, because these old trees usually have hollows in them, which furnish safe homes to animals that could not otherwise live.

One day last January, finding myself with some spare tous in one of the small towns in Northern New York, I asked the hotel-keeper if there were ‘any Squirrels to be seen about the town. He said, “No; they’re all shot off long ago”.

But I walked on beyond the houses, and there getting a view of some woods half a mile away I cut across fields in that direction. At a fence near the woods I found where a Dog had chased something that ran along the top rail. Some snow in a crotch showed the sign given below, and I knew that was the trail of either a small Gray or Red Squirrel, probably the creature chased by the Dog.

The woods turned out to be a cemetery and I found that the melancholy place was the happy home of a family of Red-Squirrels. I did not see them as it was late, but I found their trails in abundance.

They had one or two hollow trees of refuge, but they also had holes under the monuments and gravestones. This was what made me sure they were Reds: the Grays do not make holes in the ground. A quarter of a mile off was a barn, the snow on the fence between and showed that the Squirrels ran there when they needed corn.

But the most interesting thing in that graveyard was a snowdrift playground. The Squirrels had made a labyrinth of galleries in the drift. Around the entrances I found the remains of nuts and pine cones, so maybe their Winter Palace was banquet-hall as well as gymnasium, but I could not examine it fully without destroying it, so I let it alone.

This Winter Palace of the Squirrels lay between the graves of a family that had died some time before, and those of some soldiers who had been killed in the Civil War, but doubtless the Squirrels found it the merriest place on earth.

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

II. – ON TRACKS (continue)

THE SECOND CHAPTER ON TRACKS

In studying trails one must always keep probabilities in mind. Sometimes one kind of track looks much like another; then the question is, Which is the likeliest in this place?

In studying trails one must always keep probabilities in mind. Sometimes one kind of track looks much like another; then the question is, Which is the likeliest in this place?

If I saw a Cougar track in India I should know it was made by a Leopard. If I found a Leopard trail in Colorado I should be sure I had found the mark of a Cougar or Mountain Lion. A Wolf track on Broadway would doubtless be the doing of a very large Dog, and a St. Bernard’s footmark in the Rockies twenty miles from anywhere would most likely turn out to be the happen-so imprint of a Gray-wolf’s foot. To be sure of the marks, then, one should know all the animals that belong to one’s neighborhood.

The way to learn the tracks themselves is by drawing them, so that you will not come to your teacher and say, “I saw a queer track to-day; I can’t just describe it, but, oh! it was so queer”, but rather, “I saw a queer track today. There is the picture I made of it”. Then you will surely get light sooner or later.

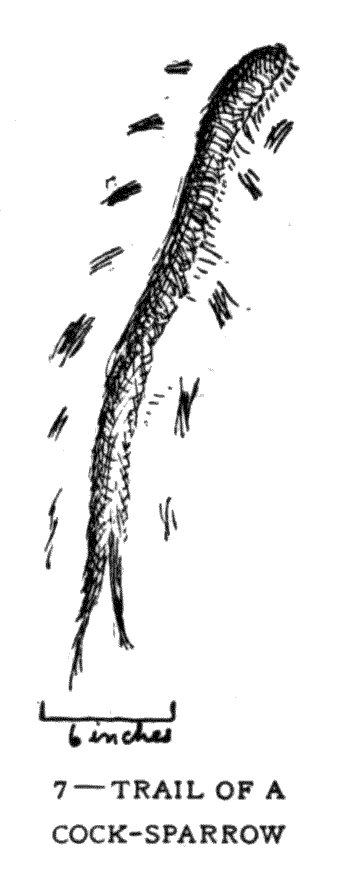

Once I was much puzzled by seeing in the snow a mark like the one shown in Cut No. 7. I had never seen one like it before, so I sketched it and put it away. Later I learned by accident that this was the trail left by a Cock-sparrow strutting in the snow before his chosen bride.

Once I was much puzzled by seeing in the snow a mark like the one shown in Cut No. 7. I had never seen one like it before, so I sketched it and put it away. Later I learned by accident that this was the trail left by a Cock-sparrow strutting in the snow before his chosen bride.

In the mud I once found another puzzle that also turned out to be a very common thing, for it was only the trail of a Turtle.

Having begun in this way you will be surprised to find, first, how many different animals are still living in your supposed barren woods; and second, how blind you have heretofore been when among them.

While drawing must be relied on mostly for track studies it is also well to remember that imprints of any kind made by the animals themselves are much more valuable. The information in a drawing is usually limited by the knowledge of the draughtsman. But the real imprint is always ready to answer new questions, and to answer them with perfect reliability. For this reason it is well to get a series of ink tracks made by the animals themselves.

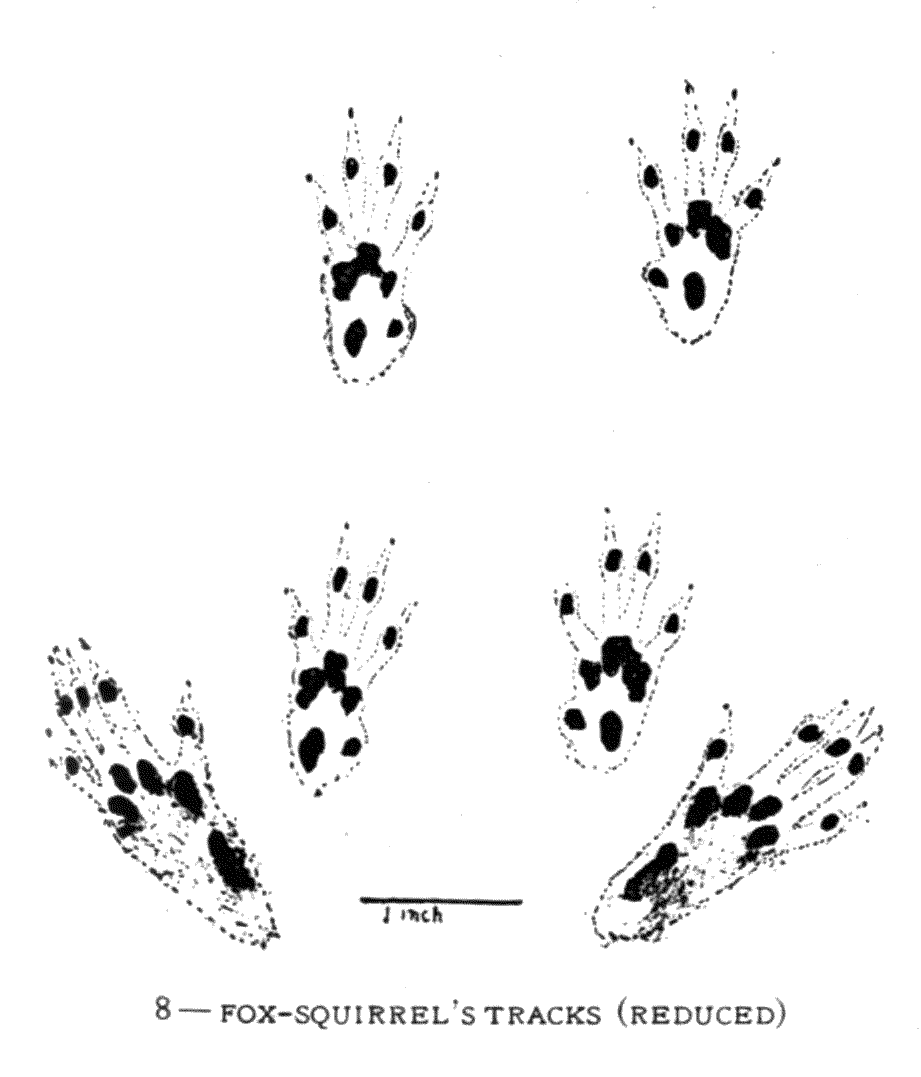

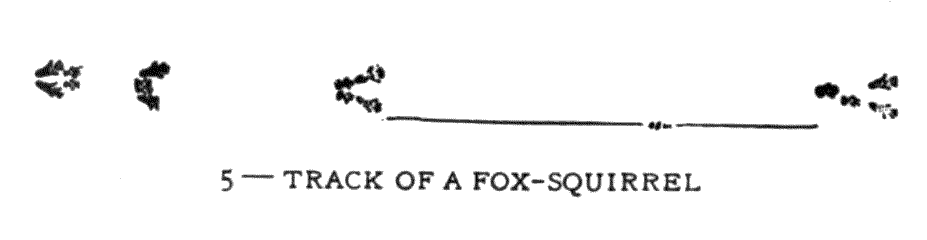

While in Marshalltown, Iowa, recently, I found a most obliging tame Fox-squirrel who supplied me with a series of records that help to explain the tracks of all our Squirrels. These were obtained by making the Squirrel run over a printer’s-inked strip of paper, then across a long white strip. This animal differed from others of his kind in turning out his hindtoes so much; I think that I could recognize his track by this, combined with his small size.

The tracks must always be compared with the foot to be rightly understood. Cuts Nos. 1 and 2 show the feet of a Fox-squirrel, life size. Cut No. 8, made direct from the Squirrel’s own track, shows its relationship to the foot.

The tracks must always be compared with the foot to be rightly understood. Cuts Nos. 1 and 2 show the feet of a Fox-squirrel, life size. Cut No. 8, made direct from the Squirrel’s own track, shows its relationship to the foot.

The track of an ordinary Fox-squirrel running over the ground is also given (Cut No.5). This shows the longest jump I ever saw made by a Fox-squirrel on the ground — that is, 48 inches clear. Their ordinary hop in going over the snow is about 14 or 15 inches clear.

The Gray-squirrel’s track differs from that of the Fox-squirrel’s chiefly in being smaller. There are many differences in their feet, as will be seen by comparing the illustrations, but these rarely show in the trail. The Squirrel type of forepaw is a 4, 3, 2 arrangement of pads — that is, 4 finger-tip pads, 3 finger-base pads, and 2 palm pads. As with us, the finger that seems to lack the base pad is the second from the outside.

The Gray-squirrel’s track differs from that of the Fox-squirrel’s chiefly in being smaller. There are many differences in their feet, as will be seen by comparing the illustrations, but these rarely show in the trail. The Squirrel type of forepaw is a 4, 3, 2 arrangement of pads — that is, 4 finger-tip pads, 3 finger-base pads, and 2 palm pads. As with us, the finger that seems to lack the base pad is the second from the outside.

One day as I walked through a small town in New England a boy addressed me by name and asked if it were possible to find any wild animals in that neighborhood. It was about one hour before sundown, so I said, “Can you, without going too far, show me a woods with a stream through it?”

He said that he could, and after a ten-minute walk we stood in a little valley full of second-growth timber. The snow was still on the ground, so I made a wide sweep and at length came. on a trail.

“What is that?” said he.

“That is a Cat track.”

“Why, I didn’t know they came away out here!”

“That may possibly be the track of your own Cat. They are such wanderers.”

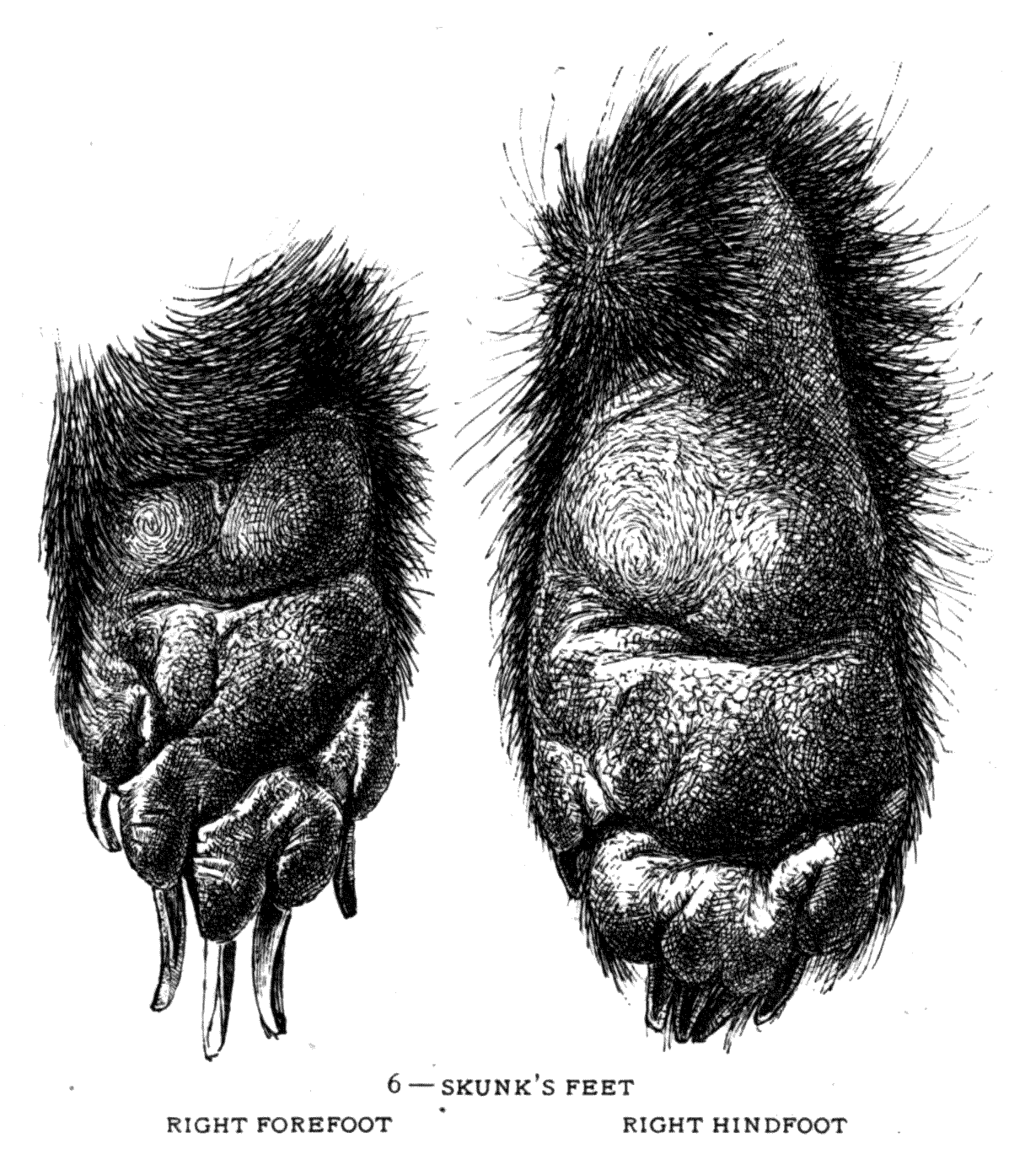

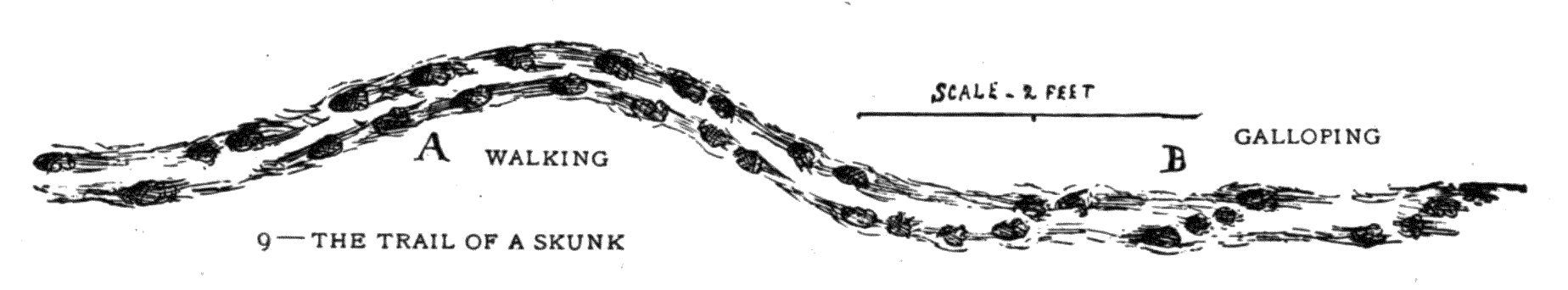

As we swung around a corner of the woods and climbed a stone fence we came on a track that is very unmistakable — the track of a Skunk.

“Yes, I knew there were Skunks about. I sometimes smelled them”, the boy said.

“Yes, I knew there were Skunks about. I sometimes smelled them”, the boy said.

We followed this for half an hour, winding in and out among the trees, sliding down banks or galloping across little hollows; once or twice going out a little way into the open, where its track was lost on the hard ground, then back into the woods, where it was very easy to read. We followed it in many wanderings; apparently it was seeking for food, but it certainly found none. Their food must be very scarce in the early spring, and that, no doubt, is why they need the immense store of fat that their bodies contain when first they are called out by the returning warm weather.

There is at least one satisfactory thing about a Skunk track. You know it will not go far. You may follow a Fox track all day and see nothing of Fox or den, but a Skunk is a slow traveler, and usually an hour’s following will show you where he lives.

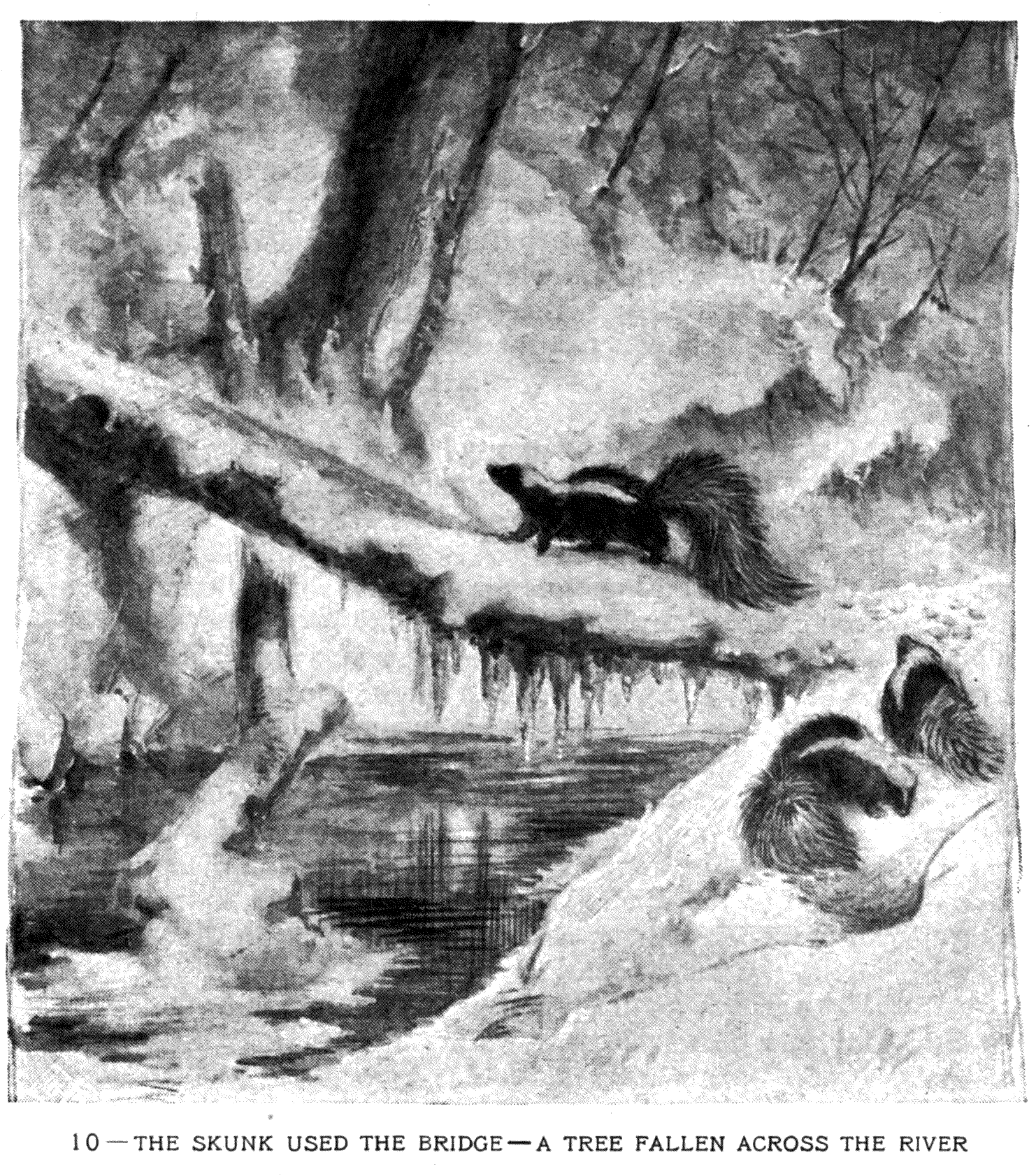

At length the Skunk track neared the stream, which was in a deep bed with steep banks. On the other side we could see several similar tracks leading to a most interesting hole that was doubtless the family headquarters. The Skunk had evidently gone home over there, but how did he cross this deep ditch with its ice-cold, unfrozen flood? A little examination showed how. He did just as any sensible animal would do when he did not wish to get wet — he used the bridge, and that bridge was simply a tree fallen across the river. I sketched it and have the drawing as an unanimal memento of an animal hunt. But I have here put in a couple of Skunks to show the family going out for a ramble (Cut No. 10).

At length the Skunk track neared the stream, which was in a deep bed with steep banks. On the other side we could see several similar tracks leading to a most interesting hole that was doubtless the family headquarters. The Skunk had evidently gone home over there, but how did he cross this deep ditch with its ice-cold, unfrozen flood? A little examination showed how. He did just as any sensible animal would do when he did not wish to get wet — he used the bridge, and that bridge was simply a tree fallen across the river. I sketched it and have the drawing as an unanimal memento of an animal hunt. But I have here put in a couple of Skunks to show the family going out for a ramble (Cut No. 10).

We traveled yet farther, then came on a new trail like that shown in Cut No. 5.

We traveled yet farther, then came on a new trail like that shown in Cut No. 5.

“There”, said I, “is the track of a Gray-squirrel. You see, the hindfoot was nearly 3 inches long — too long for a Red-squirrel, and it cannot be a Fox-squirrel, as they do not come into this region. Here is where probabilities help.”

“But there are no Gray-squirrels around here, either”, said the boy. “I have often looked and never yet saw one.”

“You think not; but see, we have here his own account of the visit; the track won’t tell a lie. He was running that way; you see the large tracks made by the hindfeet are in advance because he was going fast.”

Over the snow it was, of course, easy to tollow; but we came to a long open stretch of hard bare ground, at the north end of which was a grove of small pine trees. Around the sides were thickets of saplings, and lying up hill through the saplings at the south was a large fallen tree.

“Now”, said I, “the Squirrel would not go to those small pines because they are never hollow and have no food to offer. We cannot follow his trail here on the bare ground. Do you know of any big old trees in the neighborhood?”

He thought a minute, then said, “Yes, there are two old white oaks off this way” — and he pointed over the hill — “and some old beeches down that other way”.

“Have any of them dead tops?” said I.

“Yes, the oaks have.”

“Then that means they are hollow and the Squirrel lives there. We shall certainly find that he ran up that sloping log, since it is in line with the oaks.”

We went to the place and found the Squirrel tracks. Of course the bare log gave no record, but the trail reappeared at the end, and led, as expected, toward the two oaks. Sometimes it disappeared entirely when the Squirrel had gone aloft to travel along the branches. But we now knew his direction. At one place it came down and led to a large hole in a bank. The snow was padded about the hole. It seemed to be the residence either of a Woodchuck or a Skunk, I could not tell which. It did not smell like Skunk, but it is not usual for a Woodchuck to come out so much when the snow is deep.[5]

Why the Squirrel should busy himself about the hole I do not know. On the snow about the big oaks we found numberless Squirrel tracks of more than one size, and far up were several large holes, undoubtedly the doorways of the Squirrels’ home. These Squirrels I did not see. None of the hunters in town knew that they were there, they had become such experts at hiding. But now the boy knew their home he began to watch them, and he and they got quite well acquainted. Thus, thanks to the tracks, he got not only an insight into the life of a Gray-squirrel but also an insight into himself, and learned that it was possible to see a wild animal without wishing to kill it.

This is the sort of teaching that these wild neighbors of ours can do for us.

Suppose that every boy in America loves to “play Injun”. It was one of my greatest pleasures and I often wished for some one who could teach me more about it. That does not mean that I wanted to be a cruel savage, but rather that I wanted to know how to live in the woods as he does, and enjoy and understand the plants and living creatures that are found there. These papers are being written to teach every boy to do this and to get the most pleasure possible out of playing Red Man. One of the first things the “little brave” has to learn is trailing the Fourfoots that are so seldom seen. For that reason I begin with the tracks in the snow or mud. But we shall leave this subject now as the hot, dry, leafy months of summer are not good for trailing, and when the snow comes we can take it up again.

The principal things necessary to play Indian are a tribe of the right kind of boys, woods, one or more teepees, bows and arrows, a head-dress or war-bonnet for each, and of course a knowledge of woodcraft, but that will come later.

Almost any kind of a tent will do, though nothing else equals the teepee for comfort. One paper will be devoted to the making and painting of a real teepee. But the next — that is, the one in the July number — will treat of the Indian’s war-bonnet, how it can be made, and how each boy may win the right to wear one.

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

III. – PLAYING “INJUN”

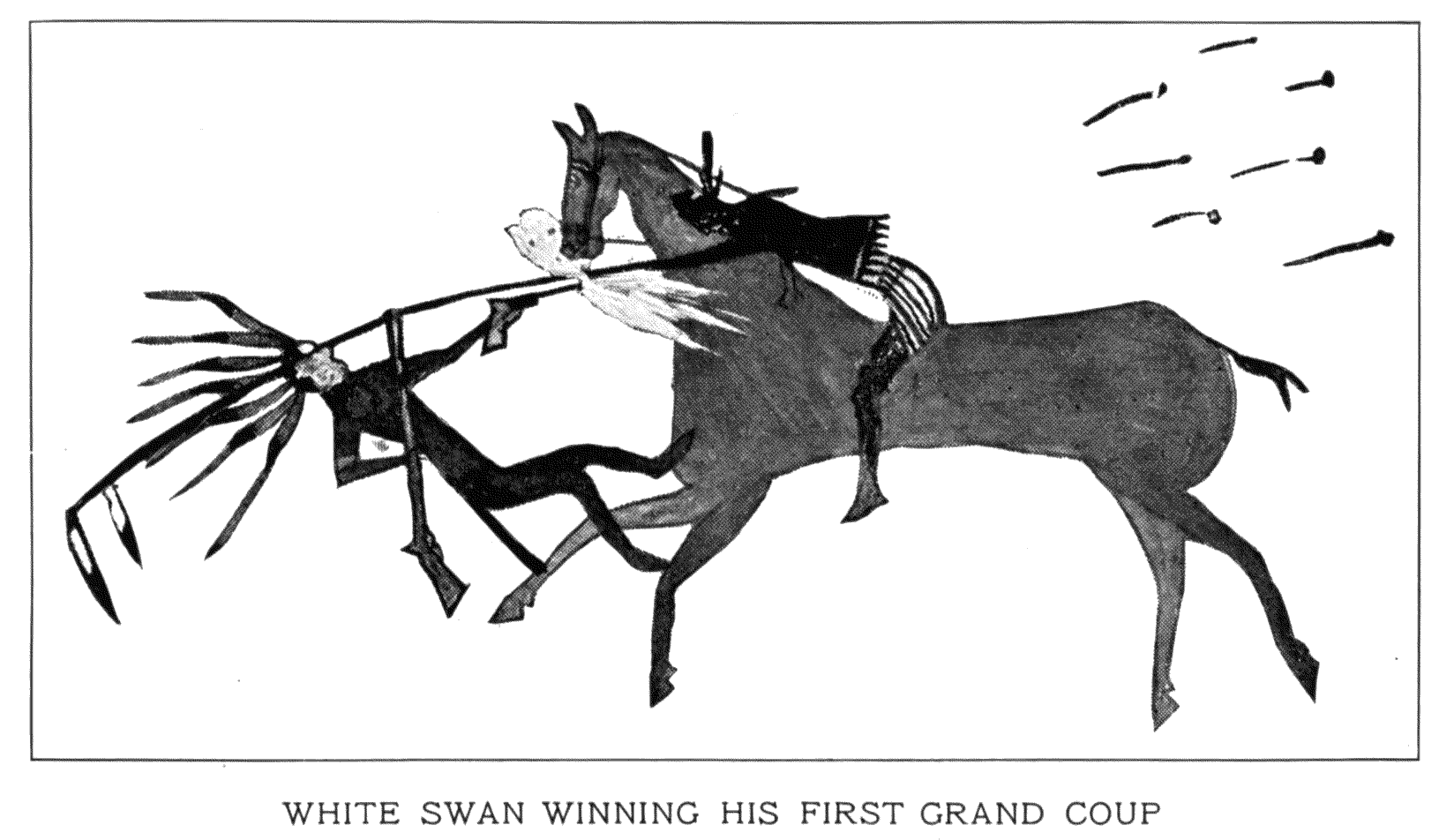

Drawn by the Crow warrior himself. Armed only with a lance, he attacked a famous Sioux chief, who had many grand coups and who was armed with a rifle and a revolver. The seven revolver shots are shown passing by White Swan as he thrusts his lance into the enemy’s eye and through his head.

The first part of his Indian outfit that the boy woodcrafter craves is sure to be the headdress, and the more he learns the more likely he is to covet it, because it is really the index of his fitness for the woods.

The typical Indian is always shown with a war-bonnet, or war-cap, of Eagle feathers. Every one is familiar with the look of this headdress, but I find that few know its meaning or why the Indian glories in it so.

In the days when the Red-man was unchanged by White-men’s ways, every feather in the brave’s headdress was awarded to him by the Grand Council for some great deed, usually in warfare. Hence the expression, “a feather in his cap”. These deeds are now called coups (pronounced coos),and when of exceptional valor they were “grand coups”, and the Eagle’s feather had a tuft of horsehair, or down, fastened on its top. Not only was each feather bestowed for some exploit, but there were also ways of marking the feathers so as to show the kind of deed.

Old plainsmen give an exciting picture in Indian life after the return of a successful war-party. All assemble in the Grand Council lodge of the village. First the leader of the party stands up, holding in his hands or having near him the scalps or other trophies he has taken, and says in a loud voice:

“Great Chief and Council of my Nation, I claim a grand coup, because I went alone into the enemy’s camp and learned about their plans, and when I came away I met one of them and killed him within his own camp.”

Then, if all the witnesses grunt and say: “Hu!” or “ How! How !” (“So — it is so”), the Council award the warrior an Eagle feather with a red tuft and a large red spot on the web, which tell why it was given.

The warrior goes on: “I claim grand coup because I slapped the enemy’s face with my hand (thereby warning him and increasing his own risk) before I killed him with my knife”.

A loud chorus of “How! How! How !” from the others sustains him, and he is awarded another grand coup.

“I claim grand coup because I captured his horse while two of his friends were watching.”

Here, perhaps, there are murmurs of dissent from the witnesses; another man claims that he also had a hand in it. There is a dispute and maybe both are awarded a coup, but neither gets grand coup. The feathers are marked with a horseshoe, but without a red tuft.

The killing of one enemy might (according to Mallery) confer feathers on four different men — the first, second and third to strike him, and the one who took his scalp.

After the chief each of the warriors comes forward in turn and claims, and is awarded, his due honers to be worn ever afterward on state occasions. All awards are made and all disputes settled by the Council, and no man would dream of being so foolish as to wear an honor that had not been conferred by them, or in any way to dispute their ruling.

In the light of this we see new interest attach to the headdress of sume famous warrior of the West when he is shown with a circle of tufted feathers around his head, and then added to that a tail of one hundred or more reaching to the ground or trailing behind him. We know that, like the rows of medals on an old soldier’s breast, they are the record of wonderful past achievements, that every one of them was won perhaps at the risk of his life. What wonder is it that travelers on the plains to-day tell us that the Indian values his headdress above all things else. He would usually prefer to part with his ponies and his wife before he will give up that array of Eagle plumes, the only tangible record that he has of whatever was heroic in his past.

We do not wish our boys playing “Injun” to do any of the dreadful things that might win a feather for the ferocious Sioux brave, but there are many achievements in woodcraft that may well take their place, and the boy’s attainments can be shown exactly by his headdress. It would be easy to give a list of one hundred grand coups that might claim feathers, but for the present I shall give only eleven, and it is understood that these are for boys under fourteen. The symbol of the feat is to be painted on the web of the feather in red or yellow paint.

We do not wish our boys playing “Injun” to do any of the dreadful things that might win a feather for the ferocious Sioux brave, but there are many achievements in woodcraft that may well take their place, and the boy’s attainments can be shown exactly by his headdress. It would be easy to give a list of one hundred grand coups that might claim feathers, but for the present I shall give only eleven, and it is understood that these are for boys under fourteen. The symbol of the feat is to be painted on the web of the feather in red or yellow paint.

- Walk 3½ measured miles in 1 hour (heel and toe) to count coup; or 4 miles for grand coup.

- Walk 1 mile in 14 minutes for coup; in 13 minutes for grand coup.

- Run 100 yards in 12½ seconds for coup; do it in 12 seconds for grand coup.

- Row (single sculls) 1 mile, still water, in 15 minutes for coup; in 12 minutes for grand coup.

- Paddle (single) 1 mile, still water, in 20 minutes for coup; in 15 minutes for grand coup.

- Swim 100 yards, still water, in 2½ minutes to count coup; or 200 yards in 5 minutes to count grand coup.

- Go 400 yards in 6 minutes; swimming 100, running 100, rowing 100 and walking 100 (in any order) for coup; do it in 5 minutes for grand coup.

- Running broad jump: 12 feet for coup; 14 feet for grand coup.

- Throw a regulation 4½-ounce baseball 50 yards for coup; 65 yards for grand coup.

- Come to camp through strange woods from a point 1 mile off in 20 minutes for coup; in 15 minutes for grand coup.

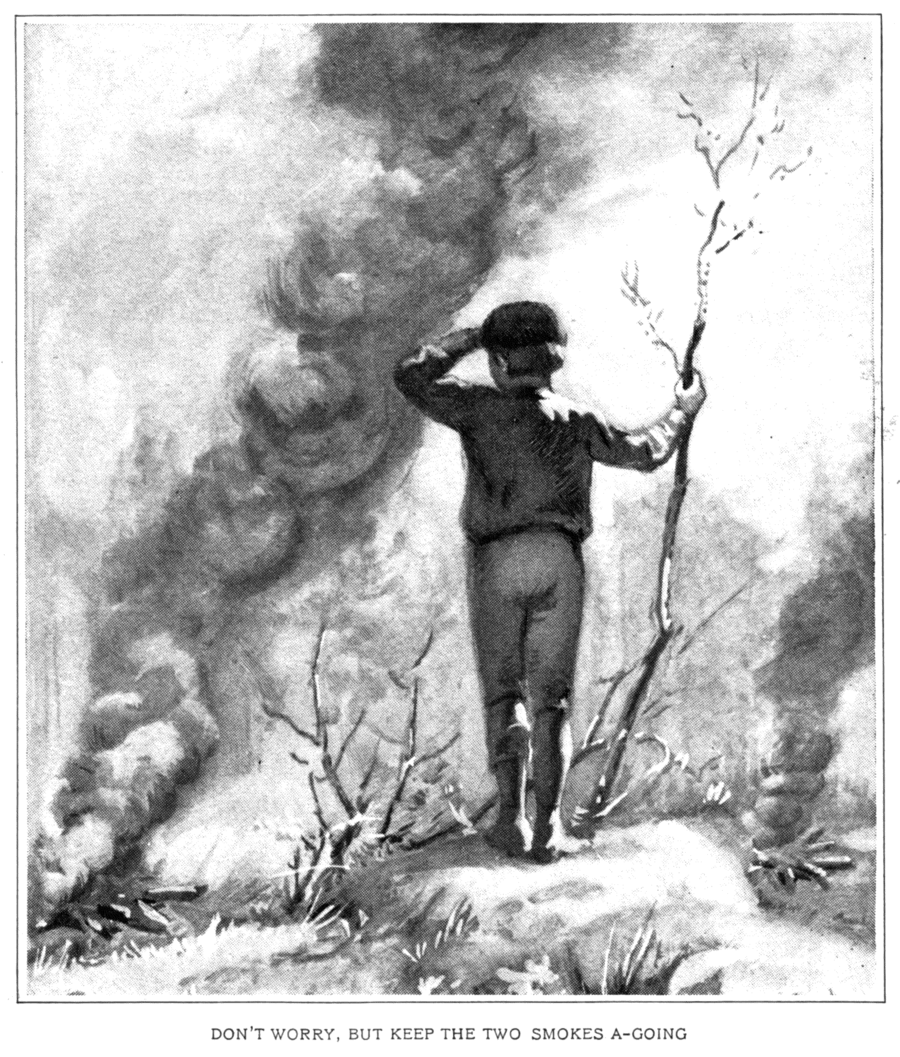

- Light 10 campfires in succession with 10 matches, all at different places, all with stuff found in the woods by the boy himself, one at least to be on a wet day. If all 10 are done on wet days, or if he does 20, of which 2 are on wet days, it counts grand coup.

I shall tell you about some other coups later.

A boy cannot reckon both coup and grand coup of the same kind.

There is also a bad coup to be counted. This is a “black feather” worn in front. It is a disgrace and is to be imposed by the Council only for very grave offenses. The high crimes of a woodcrafter are:

- Cheating;

- Killing a song-bird;

- Setting out wild-fire;

- Breaking the game-laws,;

- Rebelling;

- Wearing an honor not conferred by the Council.

The boy with the black feather cannot enter into the Council or into any of the games, but he can be made to work until he has won his way back to favor and wiped out his disgrace. The extreme punishment would be to destroy the culprit’s weapons and badges and expel him from the tribe.

In a small tribe all the members in good standing form the Council; in a large one only the chiefs or those who have won at least 20 coups. It is left to the Council to elect the Great Chief.

A newcomer is always supposed to do some feat at once to prove his fitness to be a member of the tribe.

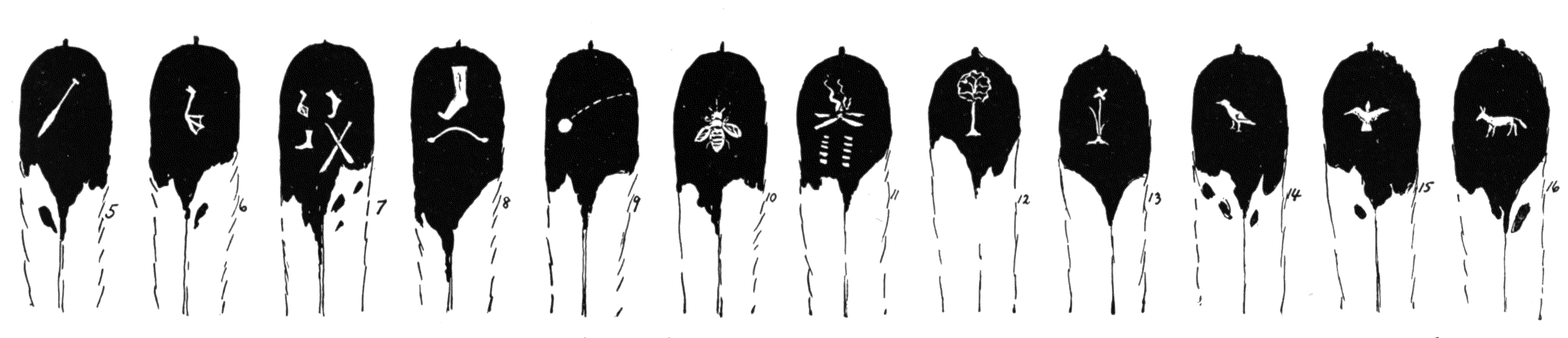

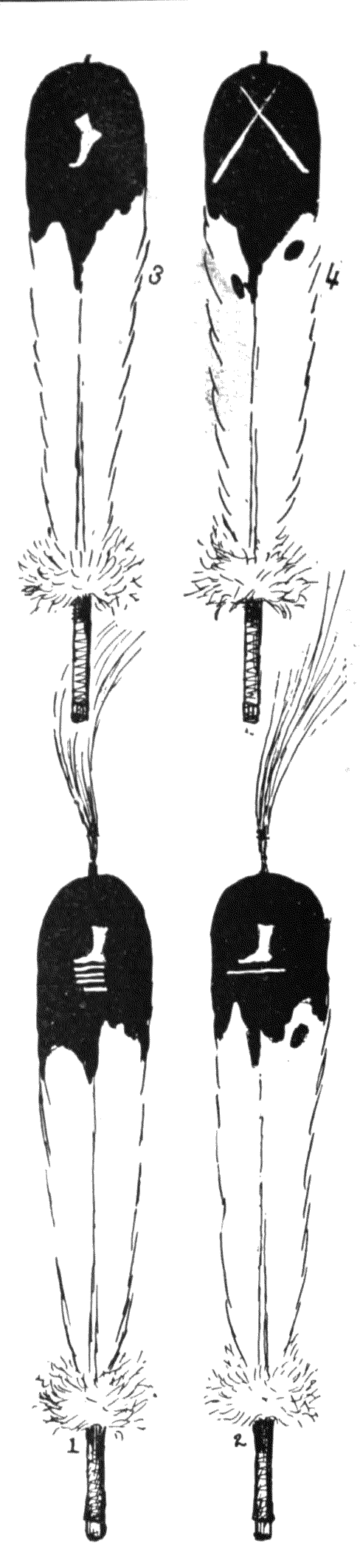

Most boys will ask how the headdress is made. Fortunately we can make it without either Eagle’s feathers or buckskin. I should be sorry to write anything that would increase the demand for these things and lead to yet more destructive hunting after the creatures that produce them. I find that all feather dealers in our large cities carry stocks of quill feathers from white Turkeys and Geese. These are very cheap and can readily be made into beautiful Eagle plumes. The Turkey feathers are the better general shape, but the Goose feathers are stronger. The other things necessary are some tan-colored calf or sheep skin — these answer as well as buckskin — some strong linen thread, shoemaker’s wax, scarlet flannel, white horsehair dyed scarlet, white down from a Goose, Turkey or other domestic bird, red or yellow oil paint, and a bottle of black, waterproof, American drawing ink. A Turkey tail feather must be trimmed to Eagle shape by cutting along the dotted lines, leaving the little point of the mid-rib. (Cut I.) Then cut off the point of the quill squarely, aiming to make the feathers of uniform size and shape. Next lay the feathers smoothly on a flat board with a light weight on the quill end to steady it, and neatly and lightly paint the upper third with black or dark brown waterproof ink on the upper side, taking care not to break the web; set this away to dry. (Cut II.)

If the ink will not “take”, paint the feather first with washing soda dissolved in water, or, better still, add a little ox-gall. Give it another coat of ink if the first dries too light. This tinting of the tip can be done by dyeing, but it is very difficult to get the feathers in good shape again after boiling them; also in dyeing it is harder to make the line of color irregular in imitation of the Eagle plume. Rub a little shoemaker’s wax on the quill, select enough of the white down to make a ruff as in Cut III, and lash it on with a fine thread well waxed. Cut a strip of leather about 5 inches long and ¼ of an inch wide; lash this with waxed thread on to the quill so as to leave a loop at the lower end (Cut IV),

the hole through to be in the same line as the web of the feather. If the quill happens to be very long this loop can be made by cutting it so (Cut V), then doubling the point “A” up into the barrel of the quill “B”. Cover the quill up to the down with red flannel, sewed on with the seam behind. This makes a coup feather.

To make a grand coup, take a wisp of red horse hair, 5 to 9 inches long, and with, perhaps, 40 or 50 hairs in it, and lash this with waxed thread or a piece of wax to the point of the mid-rib of the coup feather. Then with a needle put one fine lashing half an inch lower down on the mid-rib. (Cut VI.)

The body of the bonnet is made either as a band (Cut VII) or as a skullcap of leather, keeping the rough side out, or if the smooth side shows it should be roughened with sandpaper. The band should be 3 inches wide and 24 inches long to allow for overlap. It is fastened at the back with a lace that can be adjusted to fit. One inch from the bottom should be a row of holes in pairs, the first of each pair about 1 inch from the first of the next pair (Cut IX),

the holes big enough to take a stout string or a thin leather lace, that comes out of each hole and passes through the loop at the lower end of the feathers and in at the next nearest hole.

The feathers are held upright and the proper distance apart by a stout thread, a fine thong, or a strip of sinew that passes around through a hole in the mid-rib of each plume about 6 inches from the bottom.

It takes 20 to 25 Eagle plumes to go around the head, or it may be well to fix the number at 20 for our Indians, and no brave can be a chief until after he has won the 20 and begun on the tail. The tail foundation is a long strip of leather about 2 inches wide with holes down the middle for the thong, much like those on the head band, but usually farther apart, especially at the lower end. It is fastened into the back of the head band with a lace as shown in Cut VIII. The tie string of the tail feathers is like that of those on the head.

This is the typical war-cap or war-bonnet. All sorts of variations are made, each tribe adding its own features. This is the simplest form, and the best for our purpose — the one that shall tally for us the accomplishments of our boy woodcrafter — that shall show just what he has done.

Remember vividly a scene I once witnessed years ago in the West, when my attention was strongly directed to the significance of the war-bonnet. I was living among a certain tribe of Indians, and one day they were subjected to a petty indignity by a well-meaning, ill-advised missionary. Two regiments of United States Cavalry were camped near, and so, being within the letter of the law, he also had power to enforce it. But this occurrence was the last of a long series of foolish small attacks on their harmless customs, and it roused the Indians, especially the younger ones, to the point of rebellion.

A Grand Council was called. A warrior got up and made a strong, logical appeal to their manhood — a tremendously stirring speech. He worked them all up and they were ready to go on the warpath, with him to lead them. I felt that my scalp was in serious danger, for an outburst seemed at hand.

But now there arose a big, square-jawed man, who had smoked in silence. He made a very short speech. It was full of plain, good sense. He told them what he knew about the United States Army — how superior it was to all the Indian tribes put together, how hopeless it was to fight it— and urged them to give up the foolish notion of the warpath. His speech would not compare with that of the other. He had neither the fire nor the words — he had not even the popular sympathy, and yet he quelled the disturbance in his few sentences; and as I looked there dawned on me the reason for his power. While the gifted orator of the big words had in his hair a single untufted Eagle feather, the other, the man with the square jaw, had Eagle feathers all around his head and trailing down his back and two feet on the ground behind him, and every one of them with a bright red tuft of horsehair at its top, and I knew then that I was listening to the voice of Plenty-Coups, the most famous chief on the Upper Missouri, and I realized how a few words from the man of deeds will go further than all the stirring speeches of one who has no record of prowess to back up his threats and fiery denunciations.

So, too, our boy woodcrafter who has won a war-bonnet of a hundred plumes has a proud trophy that is evidence to all the camp of what he has done and can do.

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

IV. – ARCHERY

The modern hunting gun is an irresistible weapon of wholesale murder, and is just as deadly no matter who pulls the trigger. It spreads terror as well as death by its loud discharge, and it leaves little clew as to who is responsible for the shot. Its deadly range is so fearfully great as to put all game at the mercy of the clumsiest tyro. Woodcraft, the oldest of all sciences and one of the best, has steadily declined since the coming of the gun, and it is entirely due to this same unbridled power that America has lost so many of her fine game animals.

The bow is a far less destructive weapon, and to succeed at all in the chase the bowman must be a double-read forester. The bow is silent and it sends the arrow with exactly the same power that the bowman’s arm puts into it — no more, no less — so it is really his own power that speeds the arrow. There is no question as to which hunter has the right to the game or is responsible for the shot when the arrow is there to tell. The gun stands for little skill, irresistible force supplied from an outside source, overwhelming unfair odds, and sure death to the victim. The bow, on the other hand, stands for all that is clever and fine in woodcraft; so, no guns or firearms of any kind are allowed in our boy Indian camp.

The Indian’s bow was short, because, though less efficient, it was easier to carry than a long one. Yet itdid not lack power. It issaid that the arrow-head sometimes appeared on the far side of the Buffalo it was fired into, and there is a tradition that Wah-na-tah, a Sioux chief, once shot his arrow through a cow Buffalo and killed her calf that was running at the other side.

But the long bow is more effective than the short one. The old English bowmen, the best the world has ever seen, always shot with the long bow.

The finest bows and arrows are those made by the professional makers, but there is no reason why each boy should not make his own.

According to several authorities the best bow woods are mulberry, osage-orange, sassafras, Southern cedar, black locust, apple, black walnut, slippery elm, iron-wood, mountain ash, hickory, California yew and hemlock.

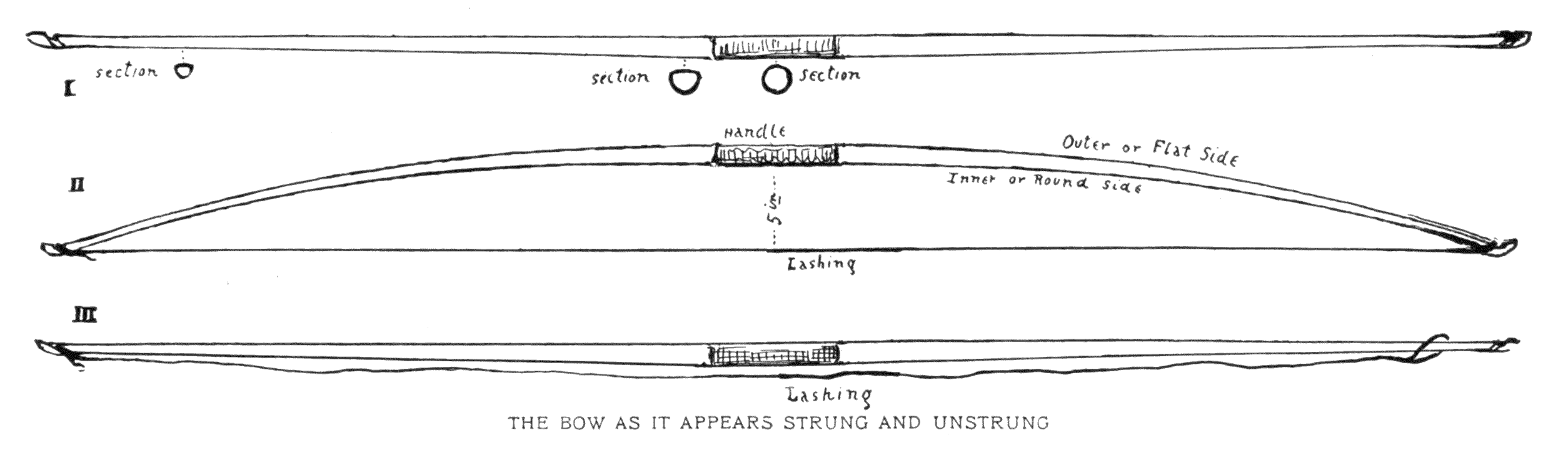

Take a perfectly sound, straight, well-seasoned stick 5 or 6 feet long (your bow should be about as long as yourself); mark off a 5-inch space in the middle for the handle; leave this round and a full inch thick; shave down the rest, flat on one side for the front and round on the other for the back, until it is about one inch wide and ¾ of an inch thick next the handle, tapering to about one-half that at the ends, which are then “nocked”, nicked or notched as shown (Cut I). These notches are for the string which is to be put on early. Draw the bow now, flat side out, not more than the proper distance, and note carefully which end bends the most; then shave down the other side until it bends evenly. The middle scarcely bends at all. The perfect shape when bent is shown in Cut XII. Trim the bow down to your strength and finish smoothly with sandpaper and glass. It should be straight when unstrung, and unstrung when not in use. Fancy curved bows are weak affairs. The bow for our boy should require a power of 15 or 20 pounds (shown on a spring balance) to draw the string 23 inches from the bow, not more.

Take a perfectly sound, straight, well-seasoned stick 5 or 6 feet long (your bow should be about as long as yourself); mark off a 5-inch space in the middle for the handle; leave this round and a full inch thick; shave down the rest, flat on one side for the front and round on the other for the back, until it is about one inch wide and ¾ of an inch thick next the handle, tapering to about one-half that at the ends, which are then “nocked”, nicked or notched as shown (Cut I). These notches are for the string which is to be put on early. Draw the bow now, flat side out, not more than the proper distance, and note carefully which end bends the most; then shave down the other side until it bends evenly. The middle scarcely bends at all. The perfect shape when bent is shown in Cut XII. Trim the bow down to your strength and finish smoothly with sandpaper and glass. It should be straight when unstrung, and unstrung when not in use. Fancy curved bows are weak affairs. The bow for our boy should require a power of 15 or 20 pounds (shown on a spring balance) to draw the string 23 inches from the bow, not more. The best string is of hemp or linen; it should be about 5 inches from the middle of the bow when strung (Cut II). The notches for the string should be ⅔ the depth of the string. If you have not a bought string make one of strong, unbleached linen thread twisted together. At one end the string, which is heaviest at the ends, should be fast knotted to the bow notch (Cut V); at the other it should have a Joop as shown in Cut IV. In the middle it should be lashed with fine silk and wax for 5 inches and the exact place marked where the arrow fits it.

The best string is of hemp or linen; it should be about 5 inches from the middle of the bow when strung (Cut II). The notches for the string should be ⅔ the depth of the string. If you have not a bought string make one of strong, unbleached linen thread twisted together. At one end the string, which is heaviest at the ends, should be fast knotted to the bow notch (Cut V); at the other it should have a Joop as shown in Cut IV. In the middle it should be lashed with fine silk and wax for 5 inches and the exact place marked where the arrow fits it.

The arrow is more important than the bow. Any one can make a bow; few can make an arrow, for, as a Seminole Indian expressed it to Maurice Thompson, “Any stick do for bow; good arrow much heap work, ugh”. Hiawatha went all the way to Dakota to see the famous arrow-maker. In England when the bow was the gun of the country, the bow-maker was called a “bowyer”, and the arrow-maker a “fletcher” (from the Norman fleche, an arrow). So when men began to use surnames those who excelled in arrow-making were proud to be called the “Fletchers”; but to make a good bow was not a notable achievement, hence few took “Bowyer” as their name.

The first thing about an arrow is that it must be perfectly straight. “Straight as an arrow” refers to the arrow itself, not to its flight; that is always curved.

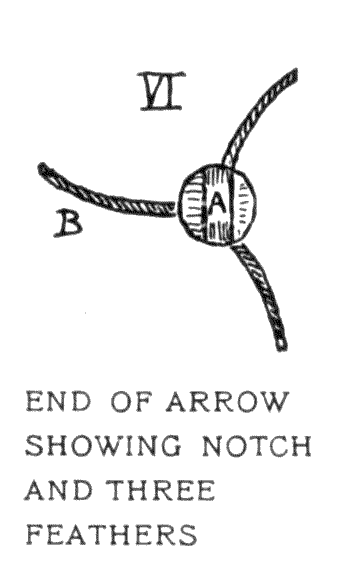

The Indians made arrows of reeds and of straight shoots of viburnum or arrow-wood, and of elder, but we make better arrows out of the solid heart-wood of hard pine for target use, and of hickory or ash for hunting. The arrow should be 25 inches long, round, and % of an inch thick, and have 3 feathers set as shown in Cut VI, about an inch from the notch. The feather B, that stands out at right angles to notch A, should always be away from the bow in shooting. This is called the cock-feather, and it is usually marked or colored in some way to be quickly distinguished.

The Indians made arrows of reeds and of straight shoots of viburnum or arrow-wood, and of elder, but we make better arrows out of the solid heart-wood of hard pine for target use, and of hickory or ash for hunting. The arrow should be 25 inches long, round, and % of an inch thick, and have 3 feathers set as shown in Cut VI, about an inch from the notch. The feather B, that stands out at right angles to notch A, should always be away from the bow in shooting. This is called the cock-feather, and it is usually marked or colored in some way to be quickly distinguished.

Turkey and Goose wing-feathers are the best that grow in our country for arrow-feathers. The Indians mostly use Turkey. With a sharp knife cut a strip of the mid-rib on which is the vane of the feather; make 3 pieces, each 2 to 3 inches long. White men glue these on to the arrow. The Indians leave the mid-rib projecting at each end and by these lash the feathers without gluing. The lashed feathers stand the weather better than those glued, but do not fly so well. The Indians use sharp flint arrow-heads for war and for big game, but for birds and small game they make arrow-heads with a knob of hard-wood or the knuckle-bone of some small animal. The best arrow-heads for our purpose are like the ferrule of an umbrella top; they receive the end of the shaft into them and keep it from splitting.

One of the best arrows I ever shot with was 28 inches long, ⁵/₁₆ of an inch thick, had a ferrule head, and very small feathers.

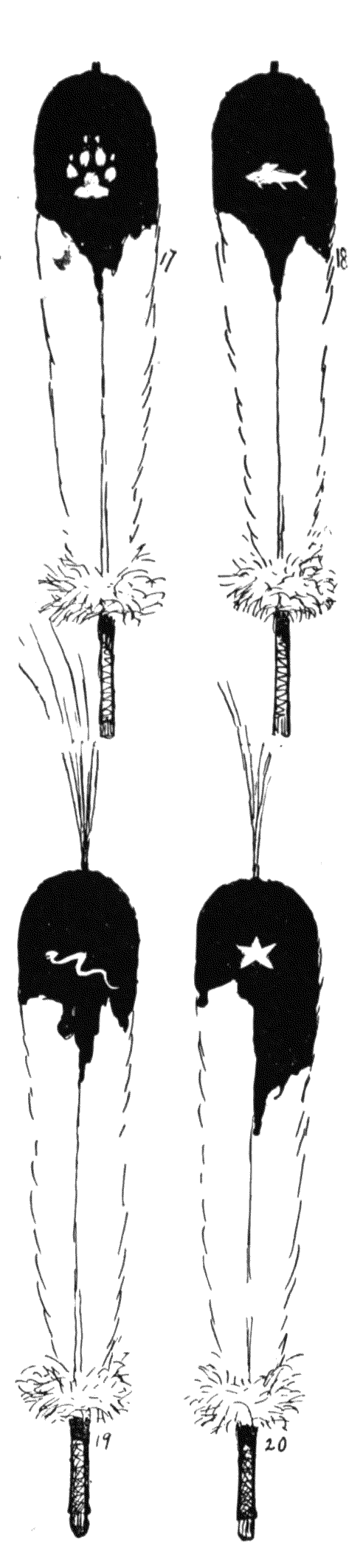

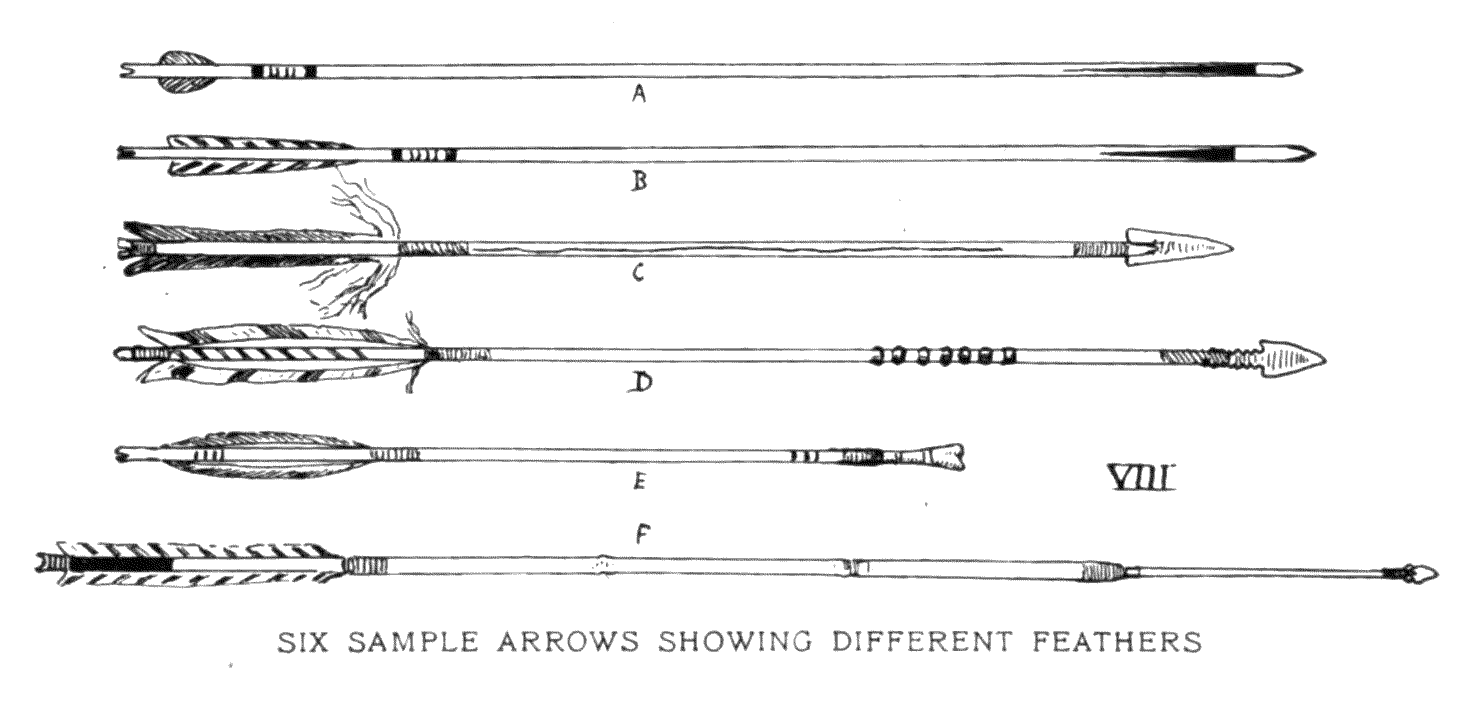

The finishing touch of an arrow is “painting” it. This is done for several purposes — first, to preserve it from damp which would twist the arrow and soften the glue that holds the feathers, second, each hunter paints all his arrows with his mark so as to know them; third, they are thus made bright-colored to help in finding them when lost. Some sample arrows are shown in Cut VIII.

A is my far-flying steel-pointed bobtail, already spoken of. B is another very good arrow with a horn point. This went even better than A if there were no wind. C isan Omaha war and deer arrow. Both head and feathers are lashed on with sinew. The long tufts of down left on the feathers are to help in finding it again, as they are snow-white and wave inthe breeze. The grooves on the shaft are to make the victim bleed more freely and be more easily tracked. D is another Omaha arrow with a peculiar owner’s mark of rings carved in the middle. E is a bone-headed bird-shaft made by the Indians of the Mackenzie River. F is a war-arrow made for Mrs. Seton by Geronimo, the famous Apache chief. Its shaft is three joints of astraight cane. The tip is of hard wood, and on that is a fine quartz point; all being lashed together with sinew.

A is my far-flying steel-pointed bobtail, already spoken of. B is another very good arrow with a horn point. This went even better than A if there were no wind. C isan Omaha war and deer arrow. Both head and feathers are lashed on with sinew. The long tufts of down left on the feathers are to help in finding it again, as they are snow-white and wave inthe breeze. The grooves on the shaft are to make the victim bleed more freely and be more easily tracked. D is another Omaha arrow with a peculiar owner’s mark of rings carved in the middle. E is a bone-headed bird-shaft made by the Indians of the Mackenzie River. F is a war-arrow made for Mrs. Seton by Geronimo, the famous Apache chief. Its shaft is three joints of astraight cane. The tip is of hard wood, and on that is a fine quartz point; all being lashed together with sinew.

There are four other things required by our archer — a smooth, hard arm-guard, or bracer, usually of hard Jeather. The Indians who use one make it of wood, grass or rawhide. In photographs of famous Indians you may often see this on the left wrist, and will remember that it was there as a protection from the blow of the bow cord. Some archers can shoot with the wrist bent so as to need no guard. The 3 middle fingers of the right hand also need protection. An old leather glove, with thumb and little finger cut away, will do very well for this, though the ready-made tips at the archery stores are more convenient. Some archers who practice all their lives can shoot without protecting the fingers.

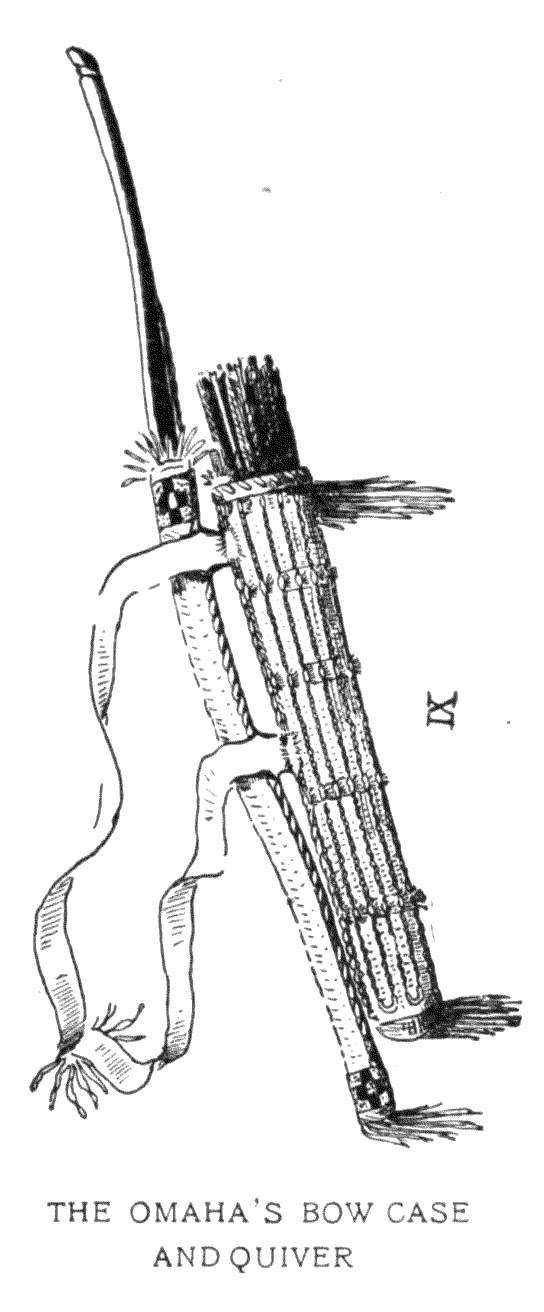

The bow case and quiver are important. Any kind of a cover that will keep them from the rain, and hang on your back, will do, but there are many little things that help to make them handy. When the cover is off the arrows should project 3 or 4 inches so that they may be more easily drawn out. The Indians often carried very beautiful quivers of buckskin ornamented with quills and beads.

The bow case and quiver are important. Any kind of a cover that will keep them from the rain, and hang on your back, will do, but there are many little things that help to make them handy. When the cover is off the arrows should project 3 or 4 inches so that they may be more easily drawn out. The Indians often carried very beautiful quivers of buckskin ornamented with quills and beads.

One day out West I saw an Omaha brave with a bow case and quiver covered with very odd material — a piece of common red and white cotton-print. When allowed to examine it I felt some other material underneath the print. After a little dickering he sold me bow, arrows, quiver and all for a couple of dollars. I then ripped open the print and found my first suspicions confirmed; for underneath, the quiver was of buck-skin, beautifully embroidered with red feathers and porcupine quills of deep red and turquoise blue (Cut IX). The Indian was as much puzzled by my preference for the quill-work as I was by his for the cotton-print.

The standard target, for men, is 4 feet across with a 9-inch bullseye, and around that 4 rings, each 434 inches wide. The bullseye counts 9, the other rings, 7, 5, 3, 1. The bought targets are made of straw, but a good target may be made of a box filled with sods, or a bank covered with sacking on which are painted the usual rings.

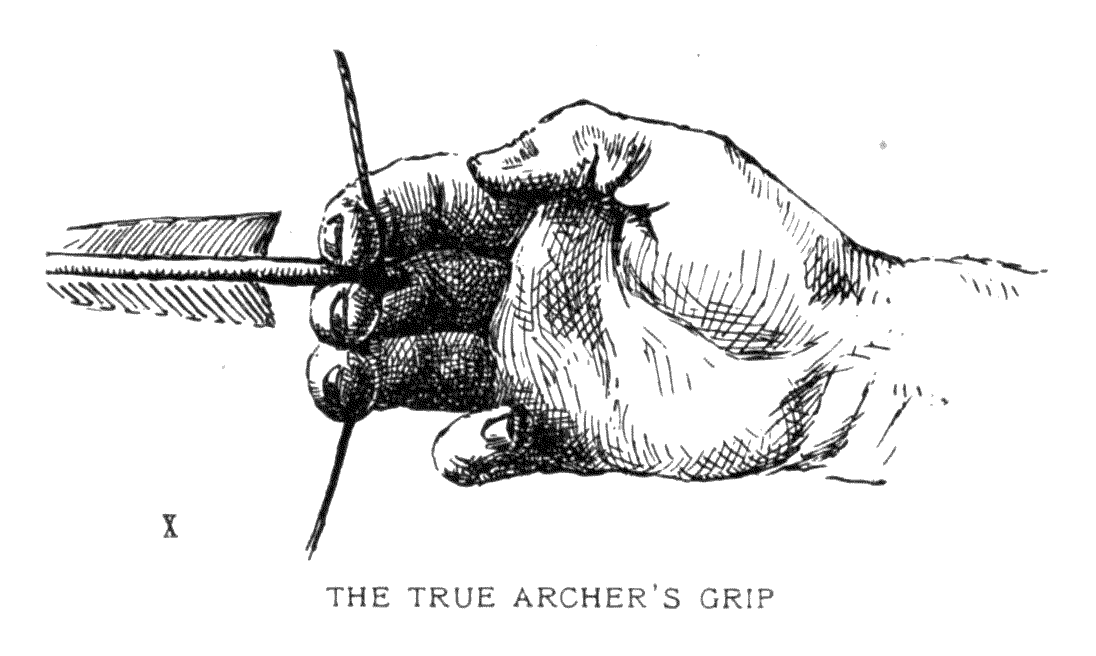

Now comes the most important point of all — how to shoot. There are several ways of holding an arrow, but only one good one. Most boys know the ordinary finger and thumb pinch, or grip. This is all very well for a toy bow, but a hunter’s bow cannot be drawn that way. No one has strength enough in his fingers for it. The true archer’s grip of the arrow is shown in Cut X. The thumb and little finger have nothing to do with it.

Now comes the most important point of all — how to shoot. There are several ways of holding an arrow, but only one good one. Most boys know the ordinary finger and thumb pinch, or grip. This is all very well for a toy bow, but a hunter’s bow cannot be drawn that way. No one has strength enough in his fingers for it. The true archer’s grip of the arrow is shown in Cut X. The thumb and little finger have nothing to do with it.

As in golf and all such things, there is a right “form”. You attend to your end of the arrow’s flight and the other will take care of itself.

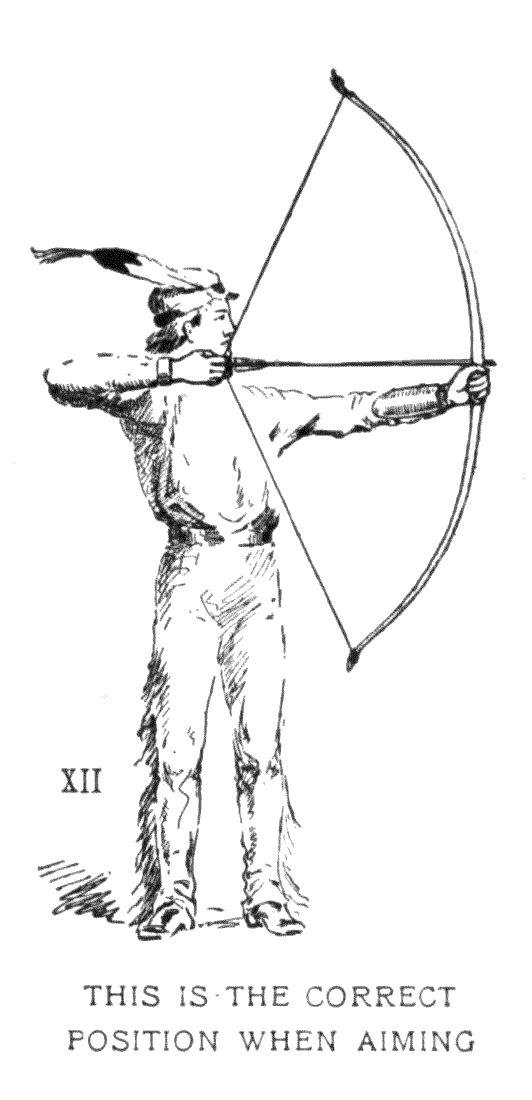

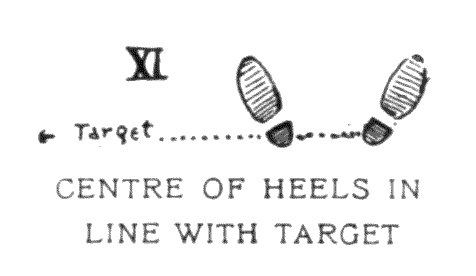

Stand perfectly straight. Plant your feet with the centres of the two heels in line with the target (Cut XI). Grasp the bow in the middle with the left hand and place the arrow on the string at the left side of the bow. Hold the bow plumb, and draw as above till the notch of the arrow is right under your eye and the head of the arrow back to the bow. The right elbow must be in the same line with the arrow (Cut XII). Let go the arrow by straightening the fingers a little, turning the hand outward at the bottom and drawing it back one inch. Always do this in exactly the same way and your shooting will be even. Your left hand should not move a hair’s breadth until the arrow strikes the target.

Stand perfectly straight. Plant your feet with the centres of the two heels in line with the target (Cut XI). Grasp the bow in the middle with the left hand and place the arrow on the string at the left side of the bow. Hold the bow plumb, and draw as above till the notch of the arrow is right under your eye and the head of the arrow back to the bow. The right elbow must be in the same line with the arrow (Cut XII). Let go the arrow by straightening the fingers a little, turning the hand outward at the bottom and drawing it back one inch. Always do this in exactly the same way and your shooting will be even. Your left hand should not move a hair’s breadth until the arrow strikes the target.

To begin shooting put the target verynear,within 15 or 20 yards, but the proper shooting distance when the archer is in good practice is 50 yards for a 4-foot target and 4o yards for a 3-foot target. A good shot, shooting 12 arrows at this, should score 50. When the archer has done it three times in succession that is, scored 150 in 36 shots — it counts coup. For grand coup he should score 225 with 36 successive shots.

To begin shooting put the target verynear,within 15 or 20 yards, but the proper shooting distance when the archer is in good practice is 50 yards for a 4-foot target and 4o yards for a 3-foot target. A good shot, shooting 12 arrows at this, should score 50. When the archer has done it three times in succession that is, scored 150 in 36 shots — it counts coup. For grand coup he should score 225 with 36 successive shots.

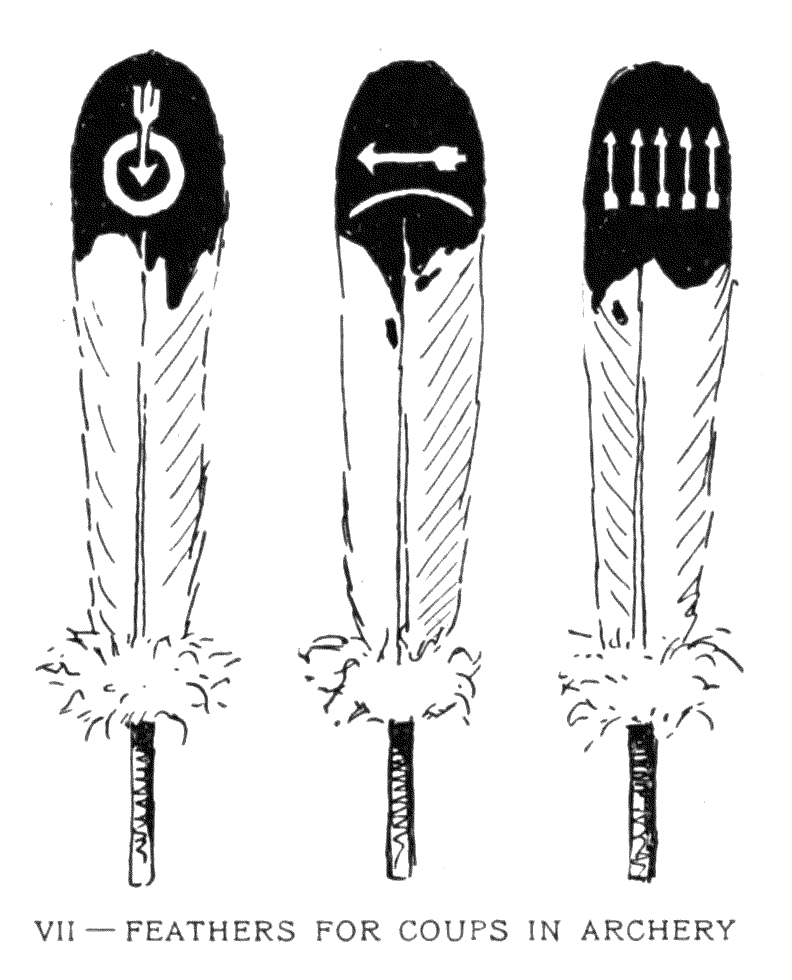

Long distance, or far shooting, is another test. To send an arrow 150 yards counts coup; 200 yards counts grand coup (Cut VII).

The Indians generally used their bows at short range, so that it was easy to hit the mark. Rapid firing was important. In their archery competitions, therefore, the prize was given to the one who could have the most arrows in the air at once. Their record, according to Catlin, was 8. We reckon coup when we can have 5 in the air, and grand coup for 7.

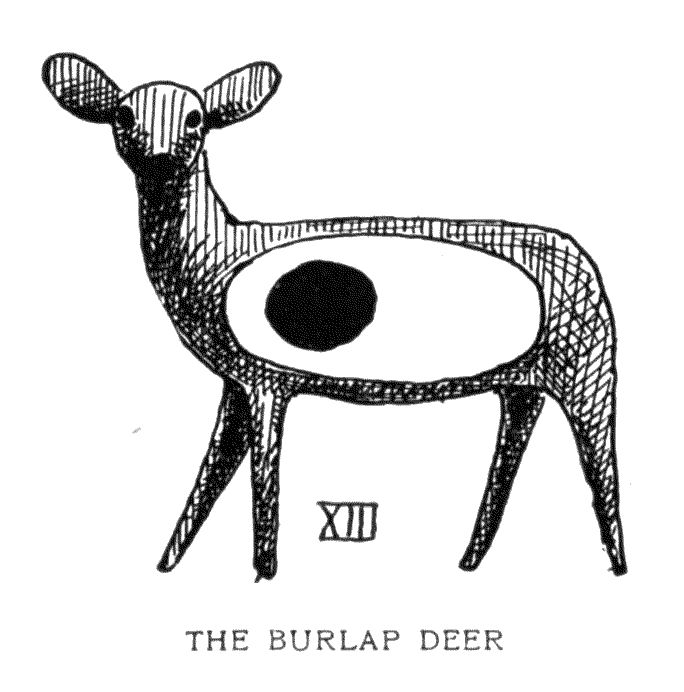

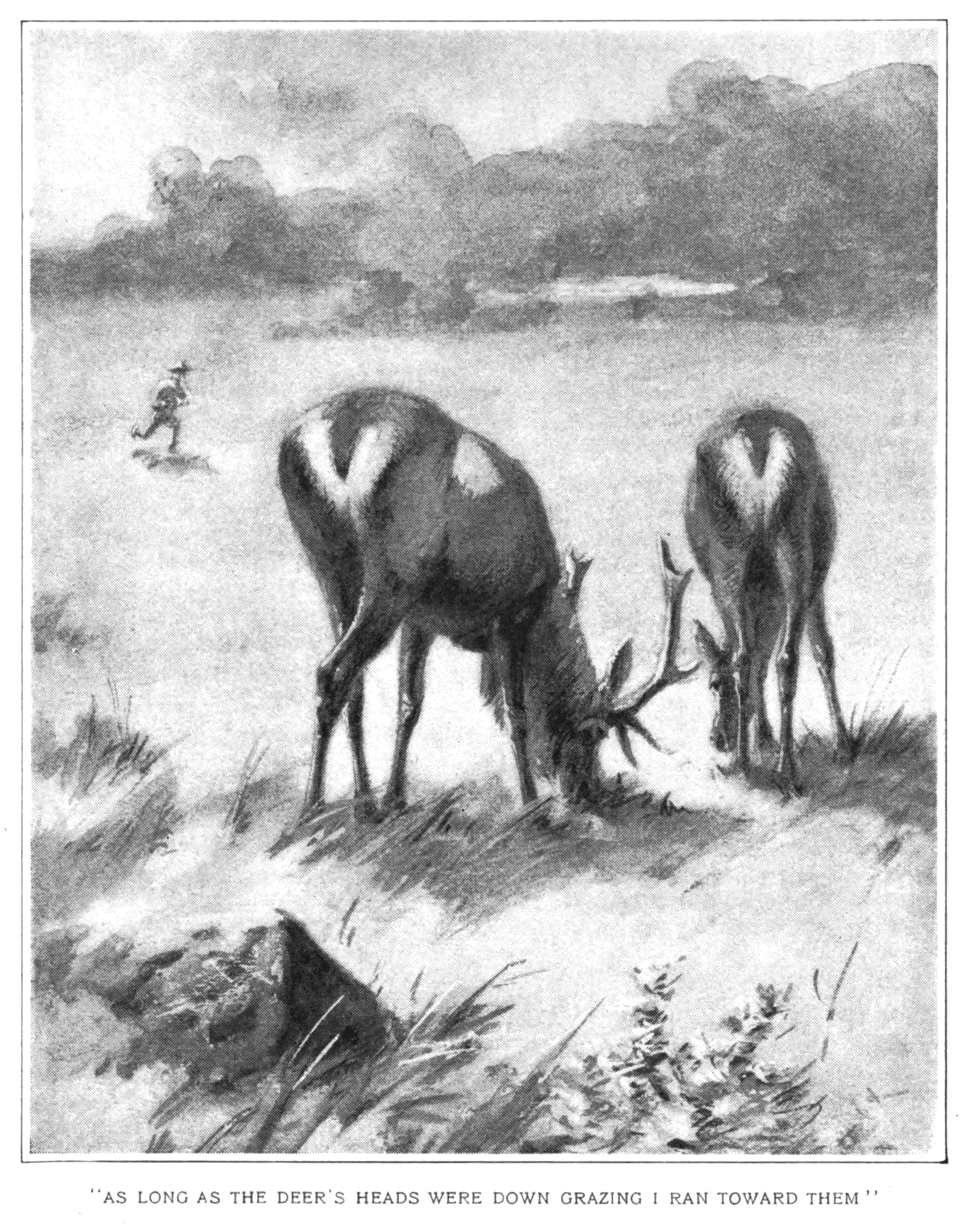

The most exciting archery game that I have ever played is hunting the Burlap Deer. Make a Deer of telegraph wire and excelsior, cased incommon burlap. No wood is used, as that breaks the arrows. A large white spot is painted on each side of the Deer, and in this, on each shoulder, a black spot, the rest being left burlap color (Cut XIII).

The most exciting archery game that I have ever played is hunting the Burlap Deer. Make a Deer of telegraph wire and excelsior, cased incommon burlap. No wood is used, as that breaks the arrows. A large white spot is painted on each side of the Deer, and in this, on each shoulder, a black spot, the rest being left burlap color (Cut XIII).

It takes three boys to play the game. One, called “the Deer-boy”, wears a red coat or shirt; the rest have their bows and a given number of arrows each. The Deer-boy is allowed one to five minutes, according to the country, to hide the Deer. When he comes back into view and shouts “ready” the hunting begins for the other two. The first one to see the Deer counts 10, but he must shoot from that place. If he misses the other walks up 5 paces nearer, or aside if he likes, and has a shot. If the second misses the first goes 5 paces from the second’s standpoint, and shoots; and so on until all arrows are gone or until the Deer is shot in the heart — that is, the black spot — which counts 10 points. A shot in the white spot — a “body wound” — counts 5; a shot in the burlap is a “scratch” and counts 1. After once the Deer is hit all the shooting must be done from the spot whence that shot was fired. If at the finish the Deer is only “scratched” the Deer-boy counts 25.

The rules are usually changed to suit different kinds of country and there is no end to the amusement that the hunt may provide. It is the sort of sport which wide-awake American boys will enjoy thoroughly day after day.

I once made a Burlap Deer stuffed with hay, but the arrows went right through and out again. Of course, an arrow that does not stick does not count, and to prevent them passing through we padded the Deer’s sides with papers. The Sunday issue of a large newspaper covered one side under the heart mark; but the shafts bounded off this as though it had been armor, and gave a very good idea of how tough a Sunday paper can be, and also showed, I suppose, that, after all, newspaper protection is a very goad thing to have.

There is no more danger in this than in any other form of target-shooting if the Deer-boy wears red and always comes out into plain sight of the shooters. The Deer should never be put on a high or rocky place, and is all the better if kept short-legged and hidden low, for then the shooters see what is beyond. If a bowman shoots at something other than the Deer he is fined 50 points.

It may be well also to assure the mother that this pursuit of a dummy, so far from developing the boy’s hunting instinct, is invariably found to work the other way. Experience shows that, like the rag raisin given to the weanling, it furnishes a harmless vent for a natural craving and at length ends all wish for the real thing.

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

V – TEEPEES

Many famous campers have said that the Indian teepee is the best-known movable home. It is roomy, self-ventilating, cannot blow down, and is the only tent that admits of a fire inside.

Many famous campers have said that the Indian teepee is the best-known movable home. It is roomy, self-ventilating, cannot blow down, and is the only tent that admits of a fire inside.

Then why is it not everywhere used? Because of the difficulty of the poles. If on the prairie, you must carry your poles. If in the woods, you must cut them at each camp.

General Sibley, the famous Indian fighter, invented a teepee with a single pole, and this is still used by our army. But it will not do for us. Its one pole is made in part of iron, and is very cumbersome as well as costly. The “Sibley” is ugly, too, compared with the real teepee, and as we are “Playing Injun”, not soldier, we shall stick to the famous and picturesque old teepee of the real Buffalo Indians.

In the “Buffalo days” this teepee was made of Buffalo skin; now it is made of some sort of canvas or cotton, but it is decorated much in the old style.

I tried to get an extra fine one made by the Indians especially as a model for our boys, but I found this no easy matter. Icould not go among the Red-folk and order it as in a department store. At length I solved the difficulty by buying one ready made from Thunder Bull, a chief of the Cheyennes.

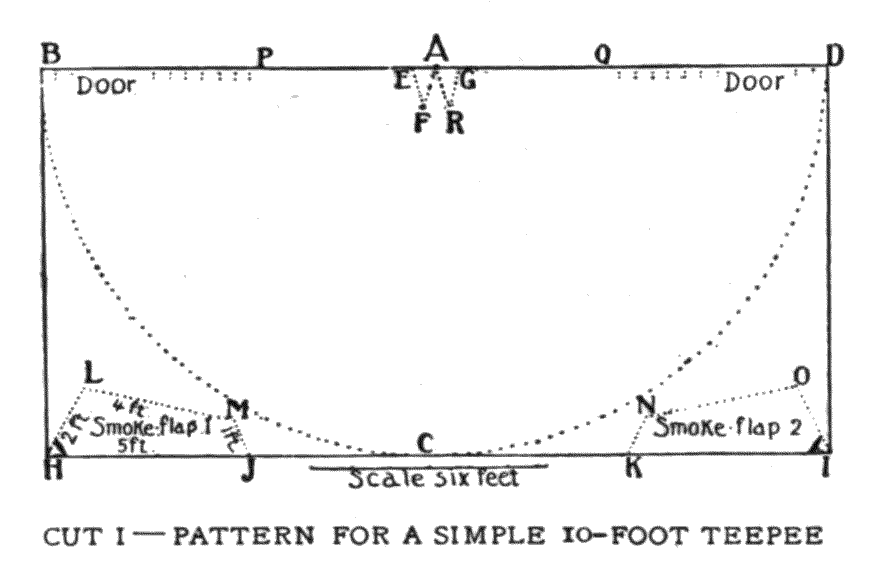

It appears at the left end of the heading on this page. This is a 20-foot teepee and is large enough for 10 boys to live in. A large one is easier to keep clear of smoke, but most boys will prefer a smaller one, as it is much handier, cheaper and easier to make. I shall therefore give the working plan of a 10-foot teepee of the simplest form — the raw material of which can be bought new for less than $4.00.

It requires 22 square yards of 6- or 8-ounce duck, heavy unbleached muslin or Canton flannel (the wider the better, as that saves labor in making up), which costs about $3.00; 100 feet of ³/₁₆-inch clothesline, 25 cents; string for sewing rope ends, etc., 5 cents.

Of course, one can often pick up second-hand materials that are quite good and cost next to nothing. An old wagon cover, or two or three old sheets, will make the teepee, and even if they are patched it is all right ; the Indian teepees are often mended where bullets and arrows have gone through them. Scraps of rope, if not rotted, will work in well enough.

Suppose you have new material to deal with. Get it machine run together 20 feet long and to feet wide. Lay this down perfectly flat (Cut I). On a peg or nail at A in the middle of the long side put a 1o-foot cord loosely, and then with a burnt stick in a loop at the other end draw the half-circle B C D. Now mark out the two little triangles at A. A E is 6 inches, A F and E F each one foot; the other triangle, A R G, is the same size. Cut the canvas along these dotted lines. From Door the scraps left over cut two pieces for smoke-flaps, as shown. On the long corner of each (H in No.1, I in No.2) a small three-cornered piece should be sewed, to make a pocket for the end of the pole.

Suppose you have new material to deal with. Get it machine run together 20 feet long and to feet wide. Lay this down perfectly flat (Cut I). On a peg or nail at A in the middle of the long side put a 1o-foot cord loosely, and then with a burnt stick in a loop at the other end draw the half-circle B C D. Now mark out the two little triangles at A. A E is 6 inches, A F and E F each one foot; the other triangle, A R G, is the same size. Cut the canvas along these dotted lines. From Door the scraps left over cut two pieces for smoke-flaps, as shown. On the long corner of each (H in No.1, I in No.2) a small three-cornered piece should be sewed, to make a pocket for the end of the pole.

Now sew the smoke-flaps to the cover so that M I. of No.1 is neatly fitted to P E, and N O of No.2 to Q G.

Two inches from the edge B P make a double row of holes; each hole is 11½ inches from its mate, and each pair is 5 inches from the next pair, except at the 2-foot space marked “door”, where no holes are needed.

The holes on the other side, Q D, must exactly fit on these.

At A fasten very strongly a 4-foot rope by the middle. Fasten the end of a 10-foot cord to J and another to K; hem a rope all along in the bottom, BC D. Cut 12 pieces of rape each about 15 inches long, fasten one firmly to the canvas at B, another at the point D, and the rest at regular distances to the hem rope along the edge between, for peg loops. The teepee cover is now made.

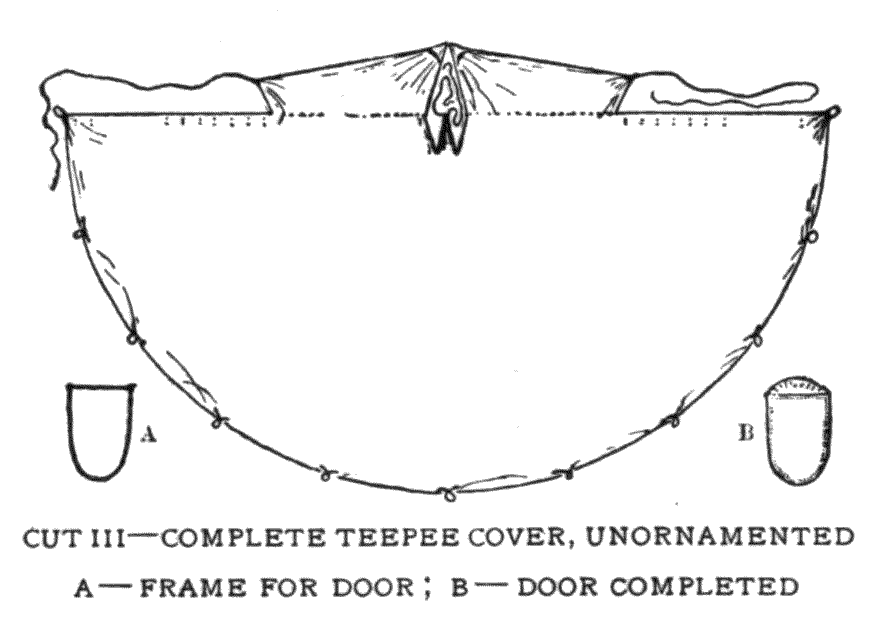

For the door (some never use one) take a limber sapling 34-inch thick and 5½ feet long, also one 22 inches long. Bend the long one into a horseshoe and fasten the short one across the ends (A in Cut III). On this stretch canvas, leaving a flap at the top in the middle of which two small holes are made (B, Cut III) so as to hang the door on a lacing-pin. Nine of these lacing-pins are needed. They are of smooth, round, straight, hard wood, a foot long and ¼-inch thick. Their way of skewering the two edges together is seen in the Omaha teepee at the end of the line.

Twelve poles also are needed. They should be as straight and smooth as possible; crooked, rough poles are signs of a bad housekeeper — a squaw is known by her teepee poles. They should be 13 or 14 feet long and about 1½ inches thick at the top. Two are for the smoke-vent; they may be more slender than the others. Last of all, make a dozen stout short pegs about 15 inches long and about 1½ inches thick. Now all the necessary parts of the teepee are made and it appears as in Cut III.

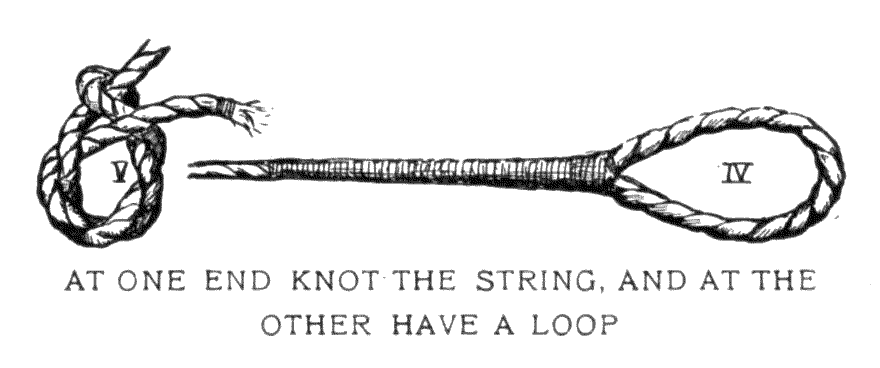

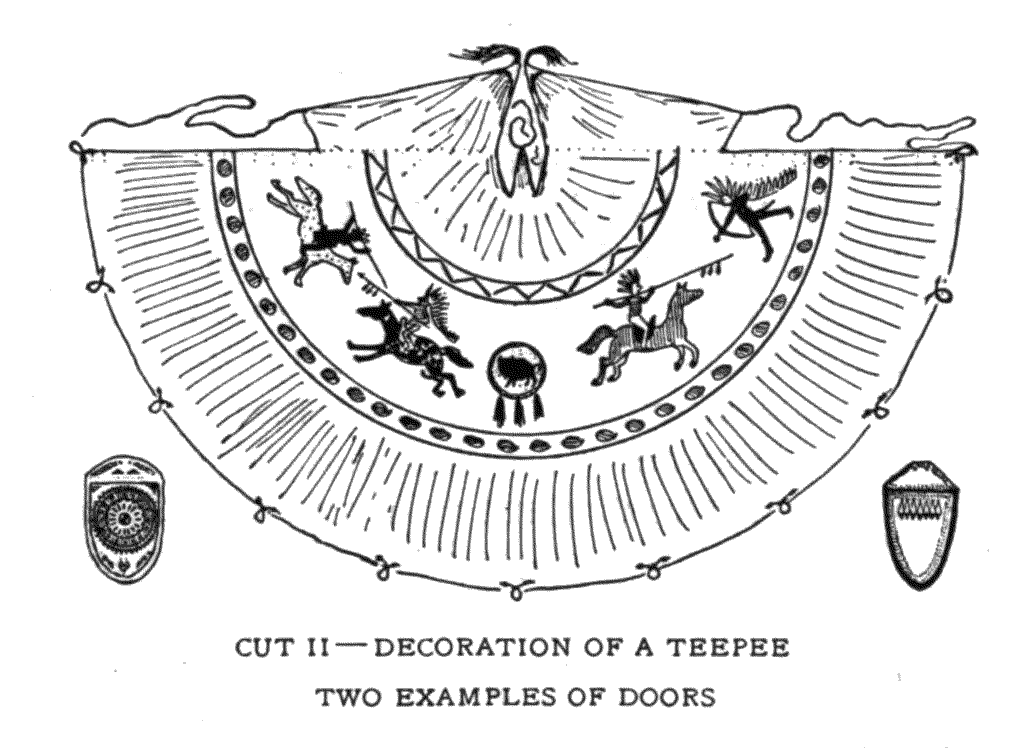

But no real Indian would live in a teepee which was not decorated in some way, and it is well to begin the adorning while the cover is flat on the ground. From the centre A at 7 feet distance draw a circle; draw another at 6½ feet, another at 3 feet and another at 2½ feet (Cut II). Make the lines any color you like, put a row of spots or zigzags in each of the 6-inch bands; then on the side, midway between A and C, draw a 1-foot circle.

In the old days every Indian had a “coat-of-arms” or “totem”, and this properly appeared on his tent. This little circle is a good place to paint your totem. The spaces at each side can be covered with figures showing the owner’s adventures, using flat colors with black outlines, but without shading. Very thin oi] colors are best.

In the old days every Indian had a “coat-of-arms” or “totem”, and this properly appeared on his tent. This little circle is a good place to paint your totem. The spaces at each side can be covered with figures showing the owner’s adventures, using flat colors with black outlines, but without shading. Very thin oi] colors are best.

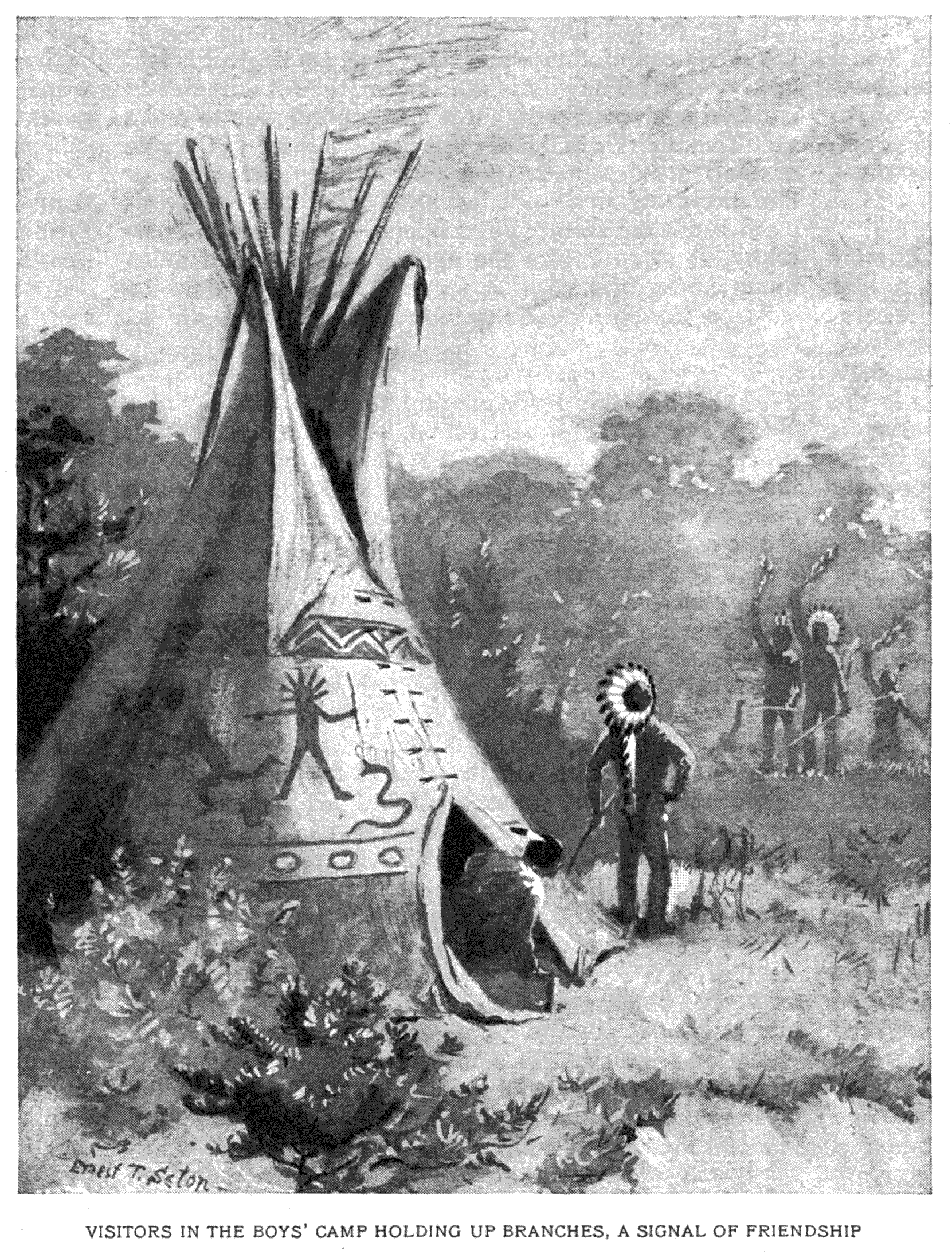

On the teepee in the picture “Visitors in Camp” is a sample of Indian style of painting. A boy went to a spring for a pail of water, but was so scared by a snake that he did not get over it for 3 days (suns). The owner of the teepee came to the rescue. This teepee was made of 27 yards of Canton flannel and 15 cents’ worth of ³/₁₆-inch grass rope; the whole costing $2.85, not including labor or paints.

On the teepee in the picture “Visitors in Camp” is a sample of Indian style of painting. A boy went to a spring for a pail of water, but was so scared by a snake that he did not get over it for 3 days (suns). The owner of the teepee came to the rescue. This teepee was made of 27 yards of Canton flannel and 15 cents’ worth of ³/₁₆-inch grass rope; the whole costing $2.85, not including labor or paints.

The pictures are usually about the middle of the wall, because when too high they get smoked, and when too low they get dirty.

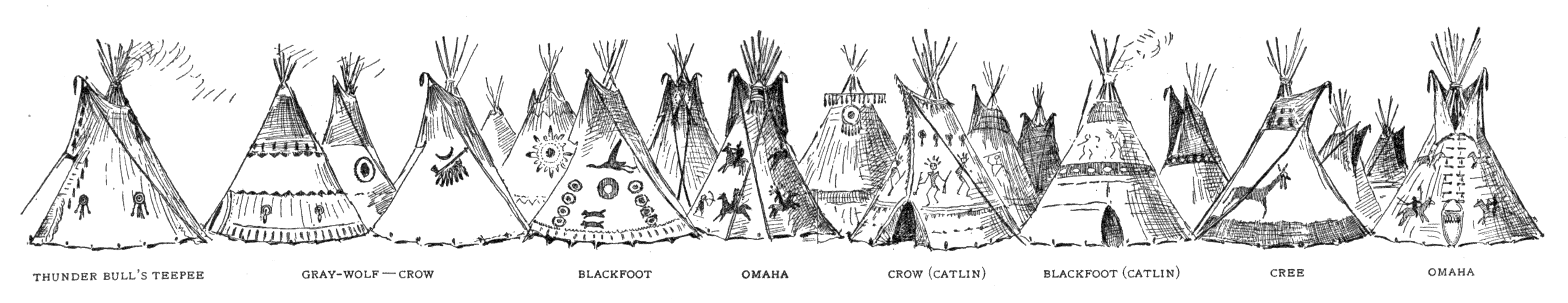

In addition to being painted the teepee is usually decorated with eagle-feathers, tufts of horsehair, beadwork, etc. In Cut II the owner’s crest, a “blue buffalo”, is shown in the small circle, and from that are three tufts for tails. On the teepees in the headband are shown many different styles of decoration and all of them were from real teepees. Scalp-locks were also used, although horsetails are more often seen now.

In addition to being painted the teepee is usually decorated with eagle-feathers, tufts of horsehair, beadwork, etc. In Cut II the owner’s crest, a “blue buffalo”, is shown in the small circle, and from that are three tufts for tails. On the teepees in the headband are shown many different styles of decoration and all of them were from real teepees. Scalp-locks were also used, although horsetails are more often seen now.

This is how the Indian tent is put up: Tie 3 poles together at a point about 2 feet higher than the canvas, spread them out in a tripod the right distance apart, then lay the other poles (except 3, including the 2 slender ones) in the angles, their lower ends forming the proper circle. Bind them all with a rope, letting its end hang dawn inside for an anchor. Now fasten the 2 ropes at A to the stout pole left over at a point 10 feet up. Raise this into its place. and the teepee cover with it, opposite where the door is to be. Carry the two wings of the tent around till they overlap and fasten together with the lacing-pins. Put the end of a vent-pole in each of the vent flap pockets, outside of the teepee. Peg down the edges of the canvas at each loop if a storm is coming, otherwise a few will do. Hang the door on a convenient lacing-pin. Drive a stout stake inside the teepee, tie the anchor rope to this and the teepee is ready for weather. In the centre dig a hole 18 inches wide and 6 inches deep for the fire.

The fire is the great advantage of the teepee, and the smoke the great disadvantage, but experience will show how to manage this. Keep the smokevent swung down wind, or at least quartering down. Sometimes you must leave the door a little open or raise the bottom of the teepee cover a little on the windward side. If this makes too much draft on your back stretch a piece of canvas between two or three of the poles inside the teepee, in front of the opening made and reaching to the ground. The draft will go up behind this.

By these tricks you can make the vent draw the smoke. But after all the main thing is to use only the best and dryest of wood. This makes a clear fire. There will always be more or less smoke 7 or 8 feet up, but it worries no one there and keeps the mosquitoes away.

You should always be ready for a storm overnight. You must study the wind continually and be weatherwise— that is, a woodcrafter — if you are to make a success of the teepee.

And remember this: The Indians did not look for hardships. They took care of their health so as to withstand hardship when it came, but they made themselves as comfortable as possible. They never slept on the ground if they could help it. Catlin tells us of the beautiful 4-post beds the Mandans used to make in their lodges. The Blackfeet make neat beds of willow rods carefully peeled, and the Eastern Indians cut piles of pine and fir branches to keep them off the ground.

Another thing of importance: Catlin says that the real wild Indians were “cleanly”. They became “filthy” when half civilized. Cleanliness around the camp should be a law. When I camp, even in the Rockies, I aim to leave the ground as undefiled as when I came. I always dig a hole, or several if need be, and say: ”Now, boys, I want all tins and rubbish put here and buried. I want this place left as clean as we found it.” This may be a matter of sentiment in the Western mountains, but in the woods near home you will find you will win many friends if you enforce the law of cleanliness.

Near the end of the row above is Gray-Wolf’s teepee. I came across this on the Upper Missouri in 1897. It was the most brilliant affair I ever saw on the Plains, for on the bright red ground of the canvas were his totems and medicine, in yellow, blue, green and black. The day I sketched it a company of United States soldiers under orders had forcibly taken away his two children “to send them to school, according to law”; so Gray-Wolf was going off at once, without pitching his tent. His little daughter, “The Fawn”, looked at me with fear, thinking I was coming to drag her off to school. I coaxed her, then gave hera quarter. She smiled, because she knew it would buy sweetmeats.

Then I said: “Little Fawn, run and tell your father that I am his friend, and I want to see his great red teepee”.

“The Fawn” came back and said, “My father hates you”.

“Tell your mother that I will pay her if she will put up the teepee.”

“The Fawn” went to her mother, and improving my offer told her that “that white man will give much money to see the red teepee up”.

The squaw looked out. I held up a dollar and got only a some look, but another squaw appeared. After some haggling they agreed to put up the teepee for $3.00. The poles were already standing. They unrolled the great cloth and deftly put it up in less than 20 minutes, but did not try to put down the anchor rope, as the ground was too hard to drive a stake into.

My sketch was half finished when the elder woman called the younger and pointed westward. They chattered together a moment and then proceeded to take down the teepee. I objected. They pointed angrily toward the west and went on. I protested that I had paid for the right to make the sketch; but in spite of me the younger squaw scrambled like a monkey up the front pole, drew the lacing-pins, and the teepee was down and rolled up in ten minutes.

I could not understand the pointing to the west, but five minutes after the teepee was down a dark spot appeared; this became a cloud and in a short time we were in the midst of a wind-storm that threw down all] teepees that were without the anchor rope, and certainly the red teepee would have been one of those to suffer but for the sight and foresight of the old Indian woman.

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Pro digitalizovaný originál viz:

Visiting the first band of Seton Indians